Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

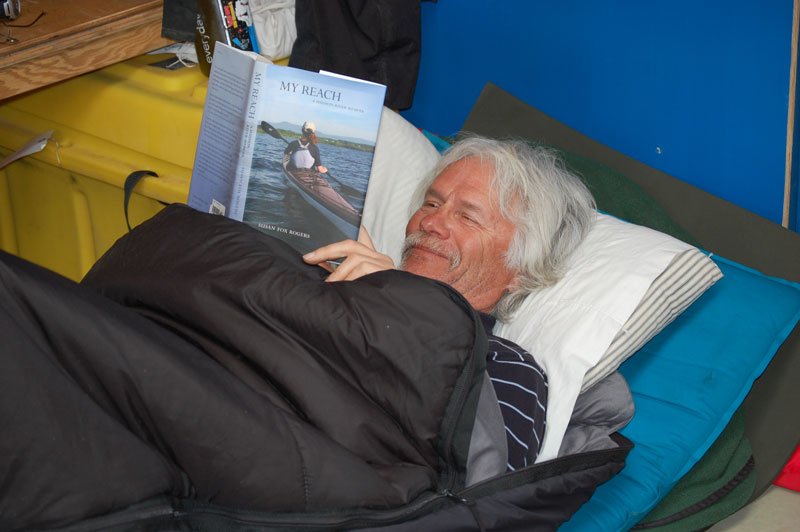

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.