In 1972, aged 12, I was invited by my cousins for a week of outdoor adventure on their island, Eagle's Nest. It is a drop of an island in Trafalger Bay, which is part of the Northern Lights Lakes in Canada. I spent that week building a tree fort, swimming in the clear cool water, and fishing.

Only on my last day did I catch a fish, an event that startled me as I had given up hope. What surprised me most was how the fish fought. Though it wasn't a large lake trout, it took everything I had in my little arms to reel it in. I remember nothing beyond bringing the fish in, the thrill and satisfaction of that. Certainly the fish was killed, cleaned and eaten. But not by me.

This July I've returned to the island with my cousin Polly and I knew fishing would be a part of our time, in between the swimming (and birding). Since 1972, I've fished but one other time so I have not perfected my cast or my technique on bringing a fish in (that trip in 1972, I lost a lot of lures, irritating the adults who had purchased those lures). Before we left on this trip, Polly left a phone message: you have to club the fish dead. I left a message in return: no way.

The island holds a sort of mythological place in my life. That week in 1972 played a big part in my early love for the outdoors. There on the island I experienced a life lived close to the rhythms of the birch and hemlock, the trout and loons. It was a life I knew I wanted. I was curious how these early, perhaps glorified, memories would measure up to what is there. And I worried that perhaps age and the mess of life would intrude on the simple beauty of being there.

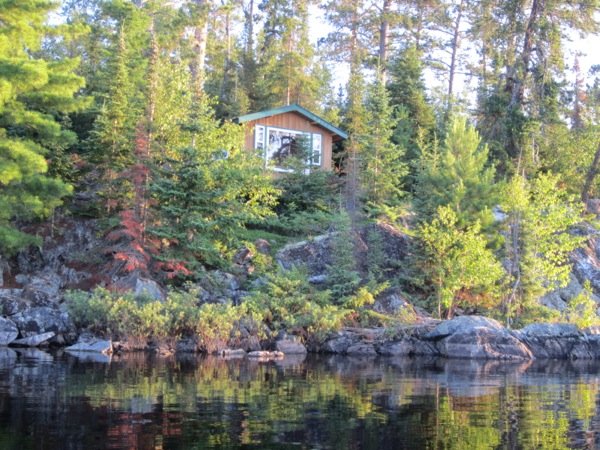

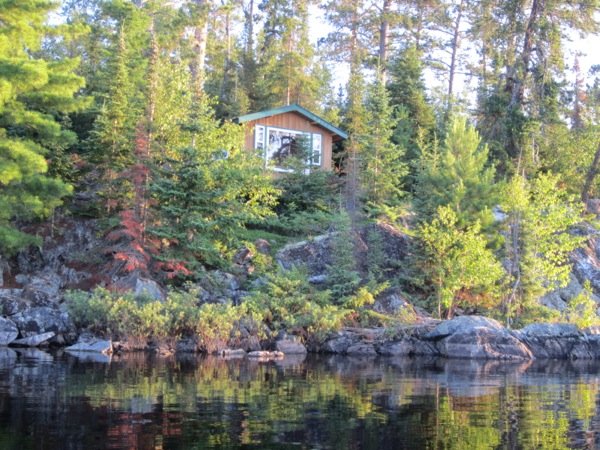

Except for a new large cabin built by my cousin Andrew, the island is remarkably the same as I remembered it. The light in the main cabin remains muted, perfect for games of backgammon or scrabble. Despite some (wonderful) improvements like a propane run refrigerator, the texture of life felt the same. There is no outside world, no internet or phone. The quiet is profound beyond all of my memories. In the late evening and through the night, the stillness was punctuated by the call of loons. Morning and evening the resident baby Merlins begged for food.

Our first full day, Polly woke me in my nest in the summer cabin, perched on a southeastern bluff, with coffee and fresh blueberry muffins. We then spent the morning swimming--naked--around the island. We pulled out on Blueberry Island and ate a few freshly ripe berries and warmed up. My hands were tingling from the cold. Our swim took hours, bobbing in the cold water, back stroke, breast stroke, a bit of a crawl. The day unfolded, endless and endlessly beautiful, except for the mosquitos. They buzzed our ears, bit our ankles and hands. These Canadian mosquitos made those I had encountered in Alaska in June seem fat, dumb and slow. These mosquitos had speed and agility on their side. I could smack one and it would rebound--flying off to bite again.

By late afternoon we were ready to venture out onto the water again, this time in a canoe. To fish. "You need to provide us with dinner, cousin," I said in mock seriousness. Polly had shopped for food for five for this week--we hardly needed any food. But I loved the idea of eating our own fish. I didn't bring up how it was going to get from the water to our plates.

We explored neighboring islands while Polly cast, and reeled in the line. The act alone felt right and good, the time meandering a pleasure.

So it surprised us both when Polly snagged the fish. It hardly struggled, but rather landed peacefully in the net I held. "Smallmouth bass," she said. It lay on the bottom of the tin canoe, without flopping or flipping. Later, we read about smallmouth bass: When hooked near the surface a smallmouth will ordinarily jump high into the air and can often shake the hook or lure from its mouth. When hooked in deep water the fish is a determined, powerful fighter, and even after it has been landed it flares its fins, clamps its jaw, and continues to look and act belligerent. The smallmouth bass is a fish that just won't quit." Really? So our fish's resigned calm became a mystery. But more: isn't fishing the most metaphorical of activities? In 1972 that fish had taught me about persistence, had given me insights into my little life, had maybe even contributed to the writer I have become. Forty years later, I wanted the same insight-inspiring sort of fight. Instead, this weak foot-long smallmouth bass had deprived me of some dazzling metaphorical insight about human nature, life and death. I was feeling mildly cheated as we made our way back to shore.

I quickly struck a deal: you kill the fish. I'll cook it. I saw that I had left Polly with the dirty work. She agreed, but she needed to be reminded of how to clean the fish. I fetched the Joy of Cooking, which contains information on killing and cleaning everything from snapping turtles to snipe and woodcock (I learn the entrails of woodcock are good flambed briefly in brandy).

Polly had no trouble scaling the fish. Then I read, as if from the Bible itself: "Next, draw the fish. Cut the entire length of the belly from the vent to the head and remove the entrails. They are all contained in a pouchlike integument which is easily freed from the flesh, so evisceration need not be a messy job." I contemplated the words integument and evisceration looking out on the water, while Polly executed her task. I read on, channeling Erma Rambauer, taking Polly through the steps of cleaning the fish. Polly's cleaning was a neat job. Erma would have been proud, and so was I.

Our fishing had not led me to thoughts on tenacity, strength, life and death. But as I stood there, looking at the lake, I saw that the real story is about cleaning the fish, facing the pouchlike integument. So much of life is about facing the pouchlike integument.

Our fish was tender and delicately flavored cooked in butter with lemon on the side. I thanked my cousin who had remembered to buy lemons, who had cleaned that fish without complaint. As we ate our simple meal, I felt that forty years had passed and yet no years had passed. We watched an orange sunset as calm settled over our isolated island.

Cousin Polly fishing; my cabin and writing retreat; sunset