Lists

And then there are the other lists in my life. The list of climbs I have scaled—this exists only in my mind. The list of mountains I have climbed in the Catskills. There are 35 over 3,500 feet and getting up all of them is a vague goal of mine. But I can never keep track of what I’ve done and so that list is both incomplete and inaccurate. The list of birds I have seen. This is a list that birders take seriously. But once again my keeping track is haphazard. Some days I come home from birding and carefully highlight the new bird in my Sibley’s and mark the date and place. But often I forget. I get home and make tea and go on with my busy life. Somehow I think I would be a better person if I could keep these lists; keeping track of my climbs, my mountains, my birds would be tending to my life. And that attention would make me more focused, more attentive to detail. Would life be neater if these lists were in order?

And then there are the other lists in my life. The list of climbs I have scaled—this exists only in my mind. The list of mountains I have climbed in the Catskills. There are 35 over 3,500 feet and getting up all of them is a vague goal of mine. But I can never keep track of what I’ve done and so that list is both incomplete and inaccurate. The list of birds I have seen. This is a list that birders take seriously. But once again my keeping track is haphazard. Some days I come home from birding and carefully highlight the new bird in my Sibley’s and mark the date and place. But often I forget. I get home and make tea and go on with my busy life. Somehow I think I would be a better person if I could keep these lists; keeping track of my climbs, my mountains, my birds would be tending to my life. And that attention would make me more focused, more attentive to detail. Would life be neater if these lists were in order?

A few days before, eight birders had trudged to the summit of the mountain in an attempt to re-find the bird. They were all expert birders and what they came up with was a robin on the summit. This big “dip,” as a birder would say, didn’t discourage me. I would find the bird.

The road into the trail head winds through the isolated and rather quaint town of Maplecrest. In these remote towns I wonder how people make their living. Some are farming, but most houses stand lonely, seemingly braced to weather a Catskill winter. The road out of town passed by an image of hurricane Irene-related destruction: houses stood cock-eyed near the creek that had expanded to four times its usual width. The pile up of boulders and trees was frightening to see, the force palpable months later. The rising, rushing water had killed one elderly woman in Maplecrest. Many of these Catskill towns are still reeling from the storm—rebuilding bridges, roads, and houses.

At the trailhead we layered on our clothes, which we then systematically took off as we started to climb. This winter, we can agree, has been spookily mild and there was but a dusting of snow on the ground. Still, it was slick and when I went down the first time I put on my micro-spikes to help me climb. At a saddle, our group parted ways, some heading for the summit of Blackhead (a peak some needed), while my friend Mary and I went for the summit of Black Dome. “Don’t worry, I’ll be quiet,” Mary promised. We had been chatting away up the hill, but I had kept an ear cocked for any sounds. All I got was silence, and a few Black-capped Chickadees.

The summit was eerily silent. We walked slowly, pished from time to time, listened, looked. If the bird wasn’t here, where might it have gone? And then out of the corner of my eye, I saw a bird fly into a spruce tree. “I saw it too,” Mary (not a birder) confirmed. She stood on the path while I walked through thick bushes toward the tree. The bird flushed and Mary pointed to where it had vanished. We compared notes on size and color—it had to be the bird!--and I felt my blood tingle with a just miss.

We settled in to eat some lunch, hoping the bird might return. But after twenty minutes of loitering we were cold and the woods were silent.

Soon, we headed downhill. I had added nothing to my lists, not a new bird or a new peak. Yet when we arrived at the car I felt that familiar elation of a day spent outdoors, of cold and exercise and wind making my blood flow, my ideas warm.

My bird list will remain messy and incomplete, like all of my lists. Perhaps in fact that is the nature of a list, to be a process, to be unfinished, to always have more I want to see or do or experience. What I can say is there are no regrets as there is nothing like a day spent among trees, my senses alert, looking but not finding a rare bird.

Paddling in Good Company

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.

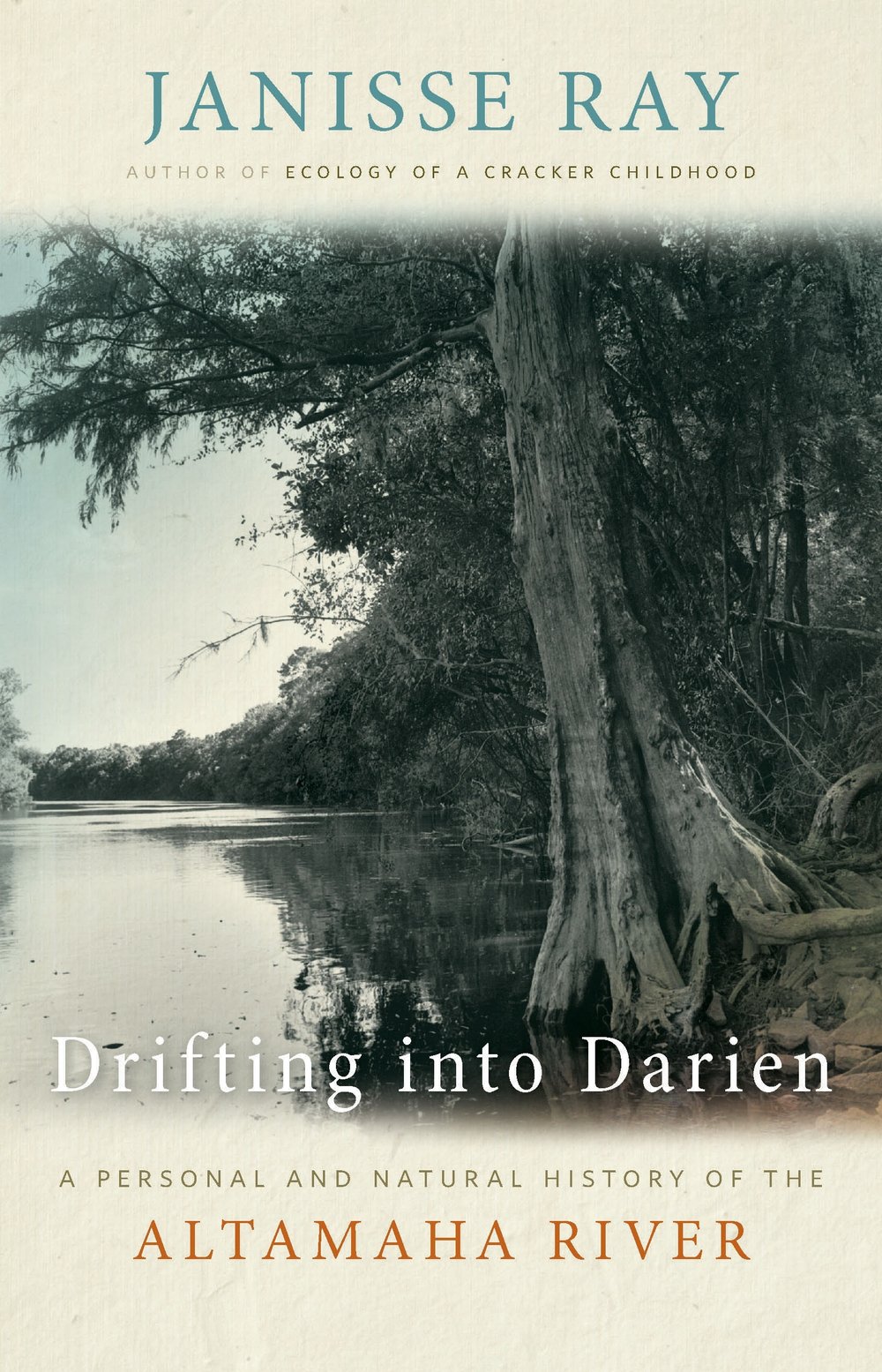

Janisse Ray claims the Altamaha river in her work Drifting Into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River and she has every right to this little-known river: she grew up alongside the river, it’s in her blood and she lives there now. The first section of the book is a wonderful narrative of an 11-day kayak down the river with a group of friends and her husband—they have recently married, so there’s a twinge of honeymoon there as they escape the “real world.” There are delicious descriptions of birds, and the best description of paddling at night (one of my favorite things to do): “A river at night is magic. The feeling is of weightlessness, of floating not just horizontally but also vertically. Humans own the daylight, animals own night. A night paddle is about breaking biorhythms. It’s about becoming animal.” Yes. The second half of the book includes essays about the river: forming the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for instance. There’s a chapter on fresh water mussels and one on the absence of bears; there are sturgeon and fishing trips and politics. And, there’s grief, loss that informs some of these essays but mostly love—for the river, for the creatures, for life.

Janisse Ray claims the Altamaha river in her work Drifting Into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River and she has every right to this little-known river: she grew up alongside the river, it’s in her blood and she lives there now. The first section of the book is a wonderful narrative of an 11-day kayak down the river with a group of friends and her husband—they have recently married, so there’s a twinge of honeymoon there as they escape the “real world.” There are delicious descriptions of birds, and the best description of paddling at night (one of my favorite things to do): “A river at night is magic. The feeling is of weightlessness, of floating not just horizontally but also vertically. Humans own the daylight, animals own night. A night paddle is about breaking biorhythms. It’s about becoming animal.” Yes. The second half of the book includes essays about the river: forming the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for instance. There’s a chapter on fresh water mussels and one on the absence of bears; there are sturgeon and fishing trips and politics. And, there’s grief, loss that informs some of these essays but mostly love—for the river, for the creatures, for life.

Mike Freeman paddled the length of the Hudson in a canoe and wrote about it in his narrative, Drifting: Two Weeks on the Hudson. He started as near to the headwaters in the Adirondacks as he could (the river emerges at Lake Tear of the Clouds near the summit of Mt. Marcy) and made his way south portaging, running rapids and once flipping over (a wonderfully dramatic moment). Amidst tales of eating more power bars than anyone should consume are lots of ideas on the environment, economy (Freeman was hit hard by the recent recession), politics, and religion (one of my favorite lines: “If there’s one thing I’ve always admired about churches, they were places people went to feel absolutely horrible about themselves.” ) The river, then, is a vehicle for ideas. Unlike me (and several of the other writers here), Freeman isn’t trying to claim the river as his in any way; he is just visiting (recently moved east from Alaska) for two weeks, to see what he could see and let his ideas wander with the river. Freeman is not an easy-going drifter—he’s on a fast course down the river, and his rants against everyone from polluters to coffee drinkers have the same sort of urgency.

John Lane, a prolific southern writer, took to the stream in his backyard in South Carolina and canoed to the sea via the Broad, Congaree and Santee Rivers. His tale: My Paddle to the Sea: Eleven Days on the River of the Carolinas is framed by a river accident in Costa Rica in which one of the guides and one paddler drown. There are two choices in the face of such a heart-breaking event: never paddle again, or paddle into your sadness and fear. Lane chose the latter. His narrative, then, is rich in thoughtfulness with depth. At the heart of it are two friendships, first with the larger-than-life character with whom he paddles the first eight days of his journey, Venable Vermont (by name alone he takes wonderful space in the book) and the his neighbor Steve Patton. Through the trip Lane confronts more rain than any person should have to weather. Though there’s a tension at the end—will he and Steve Patton make it to the ocean—there’s a wonderful easy-going feel to this story, and Lane is a great companion, a wilderness lover, “More John Muir than Teddy Roosevelt.” (Venable is a good antidote to Lane’s dreaming). There’s a lot of terrific, southern history, literary history, river’s history in this book. I came away smarter for it.

John Lane, a prolific southern writer, took to the stream in his backyard in South Carolina and canoed to the sea via the Broad, Congaree and Santee Rivers. His tale: My Paddle to the Sea: Eleven Days on the River of the Carolinas is framed by a river accident in Costa Rica in which one of the guides and one paddler drown. There are two choices in the face of such a heart-breaking event: never paddle again, or paddle into your sadness and fear. Lane chose the latter. His narrative, then, is rich in thoughtfulness with depth. At the heart of it are two friendships, first with the larger-than-life character with whom he paddles the first eight days of his journey, Venable Vermont (by name alone he takes wonderful space in the book) and the his neighbor Steve Patton. Through the trip Lane confronts more rain than any person should have to weather. Though there’s a tension at the end—will he and Steve Patton make it to the ocean—there’s a wonderful easy-going feel to this story, and Lane is a great companion, a wilderness lover, “More John Muir than Teddy Roosevelt.” (Venable is a good antidote to Lane’s dreaming). There’s a lot of terrific, southern history, literary history, river’s history in this book. I came away smarter for it.

I would say that all of these books have an environmental agenda, but the most explicit is in David Gessner’s My Green Manifesto: Down the Charles River in Pursuit of a New Environmentalism. It has the outrage of a manifesto—outrage, interestingly enough, against environmentalists (in particular he slays two: Shellenberger and Nordhaus, who wrote “The Death of Environmentalism”) whom he sees as nagging and who repeat “global warming” too frequently. Which means that Gessner has a sense of humor, a rare quality in environmental writing. What I appreciated most is that birds are his “soft spot.” And it is through birds, through watching birds (though not being a birder!) that we really observe, and in observing we “migrate outward.” This looking outward is the first “step toward falling in love.” And it is when we love something, someone, a bird or a place that we want to protect it. So Gessner’s manifesto is really a return to caring for what we know, for where we live. This gives new life to the NIMBY environmentalist (which is what I am and have continued to preach for in these days of global warming). The journey down the Charles is conversational, even casual and is filled with beer and jokes and nearly breaking the canoe in half—in this sense it will appeal to a young audience. And that is exactly who Gessner wants to get with his book; he wants to light a fire under those young butts. So it is a manifesto indeed.

First Bird of the Year (FBOY)

What everyone fails to notice is that the last—or near last—bird of the year is pretty spectacular. Take your pick—in front of us are soaring about a dozen Northern Harriers, their sleek fast bodies just above the grass line as they hunt near dusk. There’s the dark morph and the light morph Rough-legged Hawk, both impressive perched in a tree. And then, what we are all here to see: the Short-eared Owls, large floppy wings taking them to the far reaches of the grasslands. They perch in the trees, ghosts in the twilight, then take flight, like oversized moths, the flight jagged; if you tried to catch one you would miss.

What everyone fails to notice is that the last—or near last—bird of the year is pretty spectacular. Take your pick—in front of us are soaring about a dozen Northern Harriers, their sleek fast bodies just above the grass line as they hunt near dusk. There’s the dark morph and the light morph Rough-legged Hawk, both impressive perched in a tree. And then, what we are all here to see: the Short-eared Owls, large floppy wings taking them to the far reaches of the grasslands. They perch in the trees, ghosts in the twilight, then take flight, like oversized moths, the flight jagged; if you tried to catch one you would miss.

As the sun sets, an owl swoops near to us, its eyes visible in its disc-like face. It’s a phantom from the other side, a ghost from the past. We stand for a while taking in the sight of the owl, the cold and hunger push us back toward the car. When we arrive at the small parking lot, an enormous flock of Canada Geese honk their way overhead, heading for a night’s roost.

The first bird of the year is symbolic, sets the tone for the year to come. It’s a sign of good luck, perhaps. Peter and I both want the first bird to be an owl. So Peter sets a baby monitor on his front porch and we fall asleep hoping a hoot will wake us. What does wake us near dawn are coyotes howling.

January 1, I’m hesitant to go outside. “What if my first bird is a Tufted Titmouse?” I joke.

“Just plug your ears,” Peter suggests.

When I step outside the first thing I hear is the distinct caw of a Crow. Though some would rather that the crow not be their first bird, this crow cheers me. Crows are magnificent birds, smart and with a complex family arrangement. They are common enough, but still special: big and black and bold.

Our visitor from the past; photo Peter SchoenbergerWe are driving out to explore vast fields, lost empty land in the city of Kingston. Peter’s first bird flits in front of the car: Junco, that gray and white visitor from the north. Ok, so this isn’t a Barred Owl. Or, like last year, the Great Horned Owl. But not a Tufted Titmouse.

Our visitor from the past; photo Peter SchoenbergerWe are driving out to explore vast fields, lost empty land in the city of Kingston. Peter’s first bird flits in front of the car: Junco, that gray and white visitor from the north. Ok, so this isn’t a Barred Owl. Or, like last year, the Great Horned Owl. But not a Tufted Titmouse.

“At least I can be happy that my last bird of the year was a Short-eared Owl,” I muse as we hurtle down the road into our day.

“No it’s not,” Peter says. “Canada Geese.”

He’s right, of course. Keeping me honest for the New Year.

Counting Birds

I joined Peter in sector D, an area in Dutchess County that includes the vast Grieg farm where several special birds were found this fall: a Red Phalarope, a LeConte’s Sparrow and a Lincoln’s Sparrow. We rose at 4:30 to find owls. The first two locations we called left us with the deep silence of night. A final try brought two Screech Owls singing their crazy song from one side of the road, with a chorus of a Great Horned Owl hooting in from the other side.

I joined Peter in sector D, an area in Dutchess County that includes the vast Grieg farm where several special birds were found this fall: a Red Phalarope, a LeConte’s Sparrow and a Nelson’s Sparrow. We rose at 4:30 to find owls. The first two locations we called left us with the deep silence of night. A final try brought two Screech Owls singing their crazy song from one side of the road, with a chorus of a Great Horned Owl hooting in from the other side.

We pulled on mud boots to walk across the Grieg Farm to find White Crowned Sparrows in the brambles near the barn and Pipits in the far field. The Pipits were in the furrows of the field, rising and vanishing so fast, their busyness dizzying. The sun hid behind gray clouds, and the temperature hovered just around freezing. Movement kept our spirits and temperature up.

The day unfolded like the treasure hunt that it is: the Cooper’s Hawk we for a moment thought might be a Goshawk; the Yellow-Rumped Warbler that flew off before we all got a good look; the Canada Geese that in fact were an enormous flock of Wild Turkey; the Bald Eagle that flew over the car; the Red Shouldered Hawk sitting serene and nearly invisible in a field; the chorus of Grackles, 2,500 strong; the Swamp Sparrow that Peter knew would be hiding out in a far swampy area of Grieg Farm.

Except for Grieg Farm most of the area we were counting in is rural, farmland, ragged forests, or small pockets of development in what was once an apple orchard. It’s not a place you’d come to in order to bird. And yet here we were, finding a wonderful range of birds—forty-eight species by the end of the day.

We got in and out of the car a hundred times, walked over five miles in fields and on roads, got cold, then hot, ate snacks to keep us going and talked about birds as we peered out the window looking for movement, shape, scoured the sky for a Vulture. “This is where we should find a Shrike,” we said again and again as we passed open, busy areas. But, the Shrike was not where it was supposed to be.

Vanessa followed Cathy’s gaze and smiled. “A Rusty Blackbird!” A great find late in the day. Perhaps our best bird. I was delighted to realize how all four of us were needed to see, to identify, to count these birds. We were a great team.

But what I also realized is that as a person who associates animal life, bird life with natural places—with the Tivoli Bays (where they found nine Screech Owls!), for instance—that birds in fact are everywhere, anywhere. I’ve learned this again and again, that sometimes just a slice of good habitat is all a Rusty Blackbird needs. But this is so counter to all of my romantic notions of nature and its sacredness, my desire to see huge swaths of wilderness for the birds, other animals, for us. Seeking birds on count day takes me onto roads and fields and in these moments wild and what I consider human or built merge or alternate. The line isn’t so clear out there. I like that the lines of my thinking need to be redrawn as well.

Of course the birds don’t know of these distinctions I make between what is nature and not. They just know where they can find food, shelter, a place to spread their wings. Is that not what I do as well? What we all do?

There’s something to learn from counting birds; there’s something to learn from birds.