The Second Book

My first book, My Reach: A Hudson River Memoir, appeared one year ago this month. In this year of publication, I have read to kayaking groups, and Hudson River enthusiasts, devoted library goers, and AARP members. I stumbled through an NPR interview and spoke to local papers. It’s been a lot of fun, being in the world, telling the story of writing my book.

My first book, My Reach: A Hudson River Memoir, appeared one year ago this month. In this year of publication, I have read to kayaking groups, and Hudson River enthusiasts, devoted library goers, and AARP members. I stumbled through an NPR interview and spoke to local papers. It’s been a lot of fun, being in the world, telling the story of writing my book.

What I never fail to mention in my talks is that when I set out to write the book, I knew nothing about kayaking and nothing about writing a book. People are in awe that I just plunked my boat in the water and stroked off toward the far shore. But no one says, wow, you sat down in a room by yourself and wrote every single word of a book? That, for me, is the bravest thing I’ve done. I gave up writing this book dozens of times—it was just too hard (the file I kept the manuscript in is labeled: Keep Trying). I say that it took me seven years to write this book, but really, it took me a lifetime. So when I hold my book and read from it, I think, miraculous, with all sincerity.

After I read, someone from the audience inevitably asks: what’s the next book? The next book? The question is a kind one—implied is, “I liked this, I could read more.” Or maybe I am flattering myself—maybe the audience is simply polite. But my response is, “really, I have to do this again?” One book seems plenty, like people who decide that one child is just right. But when you write a book, apparently people think you should write another. In fact, I think I should write another. The problem is, I’m not.

My first book, My Reach: A Hudson River Memoir, appeared one year ago this month. In this year of publication, I have read to kayaking groups, and Hudson River enthusiasts, devoted library goers, and AARP members. I stumbled through an NPR interview and spoke to local papers. It’s been a lot of fun, being in the world, telling the story of writing my book.

My first book, My Reach: A Hudson River Memoir, appeared one year ago this month. In this year of publication, I have read to kayaking groups, and Hudson River enthusiasts, devoted library goers, and AARP members. I stumbled through an NPR interview and spoke to local papers. It’s been a lot of fun, being in the world, telling the story of writing my book.

What I never fail to mention in my talks is that when I set out to write the book, I knew nothing about kayaking and nothing about writing a book. People are in awe that I just plunked my boat in the water and stroked off toward the far shore. But no one says, wow, you sat down in a room by yourself and wrote every single word of a book? That, for me, is the bravest thing I’ve done. I gave up writing this book dozens of times—it was just too hard (the file I kept the manuscript in is labeled: Keep Trying). I say that it took me seven years to write this book, but really, it took me a lifetime. So when I hold my book and read from it, I think, miraculous, with all sincerity.

After I read, someone from the audience inevitably asks: what’s the next book? The next book? The question is a kind one—implied is, “I liked this, I could read more.” Or maybe I am flattering myself—maybe the audience is simply polite. But my response is, “really, I have to do this again?” One book seems plenty, like people who decide that one child is just right. But when you write a book, apparently people think you should write another. In fact, I think I should write another. The problem is, I’m not.

The second book is a treacherous thing. How many times has a writer put out their first book to good success, only to rush out the second book and have it be mediocre? Especially for those of us who publish later in life (I was 50 when my book came out—a fitting celebration of this landmark year), the first book often is a life-book, the one book. That, no doubt, is my situation. Still, a writer writes and I’ll keep writing. And now that I’ve written a book, another should be waiting in the wings.

I have a lot of friends who seem to be able to do this. As one book comes out, another is nearing completion. Then there are those miracle writers who churn out a book a year. I’d be much more likely to kayak around the globe.

Before I wrote My Reach, what I wrote were sentences that became paragraphs that morphed into pages, then something I called essays. I write essays, I said. I thought that alone an accomplishment. One day, I noticed that all of my essays centered on what I did, which was kayak on the Hudson River. They were filled with adventures and mis-adventures, Bald Eagles and snapping turtles, cement and ice factories. I strung these essays together, gave them shape. It was then that I noticed that the story of my parents lurked at every turn. I brought them into the foreground. I was lucky to find a real editor at Cornell University Press, a man with a pencil who wrote comments in the margins like “cliché!” or “you can do better,” or “we need to hear more about your mother.” I was grateful for it all.

What’s the next book? My editor emails me. Give me a call.

The question makes it sound easy. I thought, after doing it once, it would be not easy, but easier. I’d know the pitfalls, skirt some endless revisions. I’d head into a book with an outline, or at least a plan, rather than feel my way through the dark.

But these past few months, as I’ve sat down day after day to write the next book, I’ve encountered a whole other problem.

I’ve been thinking of writing a book--that’s the problem. When what I write are sentences, paragraphs, essays.

Somewhere in the silence of this summer, I’ve started to write essays again. But it took a lot of silence, sitting on an island in Canada (thanks to cousin Polly!) where I had no internet, no phone. I call it the silence of space, and it’s something I crave and something I know is rare. You can find it in small pockets around the world. It exists in writer’s colonies—I have been lucky to attend two, Ucross and Hedgebrook—where the silence of space greets you at your cabin door. It is both overwhelming and delicious.

The subjects of my summer essays do not neatly line up as they did with my Hudson River kayaking essays. There’s one essay about birding in Alaska, and another about being from State College, Pennsylvania in the wake of the Sandusky affair, and another about dating men after years of dating women, and one about the grandfather I did not know, and the photograph I have of him standing next to Hitler. There’s not a kayak, river, or snapping turtle to be found in these essays.

As I wrote, I loved searching for the next word; I enjoyed watching my ideas unfold. I surprised myself a few times, suffered a bit, and sweated at my desk through the hot summer months. It is possible, but unlikely, that one of these essays will extend and become a book. But after a year of trying to write a book, I now realize that isn’t what matters.

Despite all that I learned while writing a book, I feel like I’m heading out into the dark, holding onto a faith that my literary excursions will take me some place beautiful. It’s hard, holding onto this faith, whether it’s your first essay or your first book. Or your second book. And my guess is, the third book too and on down the line (maybe I’ll get there!). But what matters is sitting down every day and writing those sentences, searching for the next word, and watching my ideas unfold.

Paddling in Good Company

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.

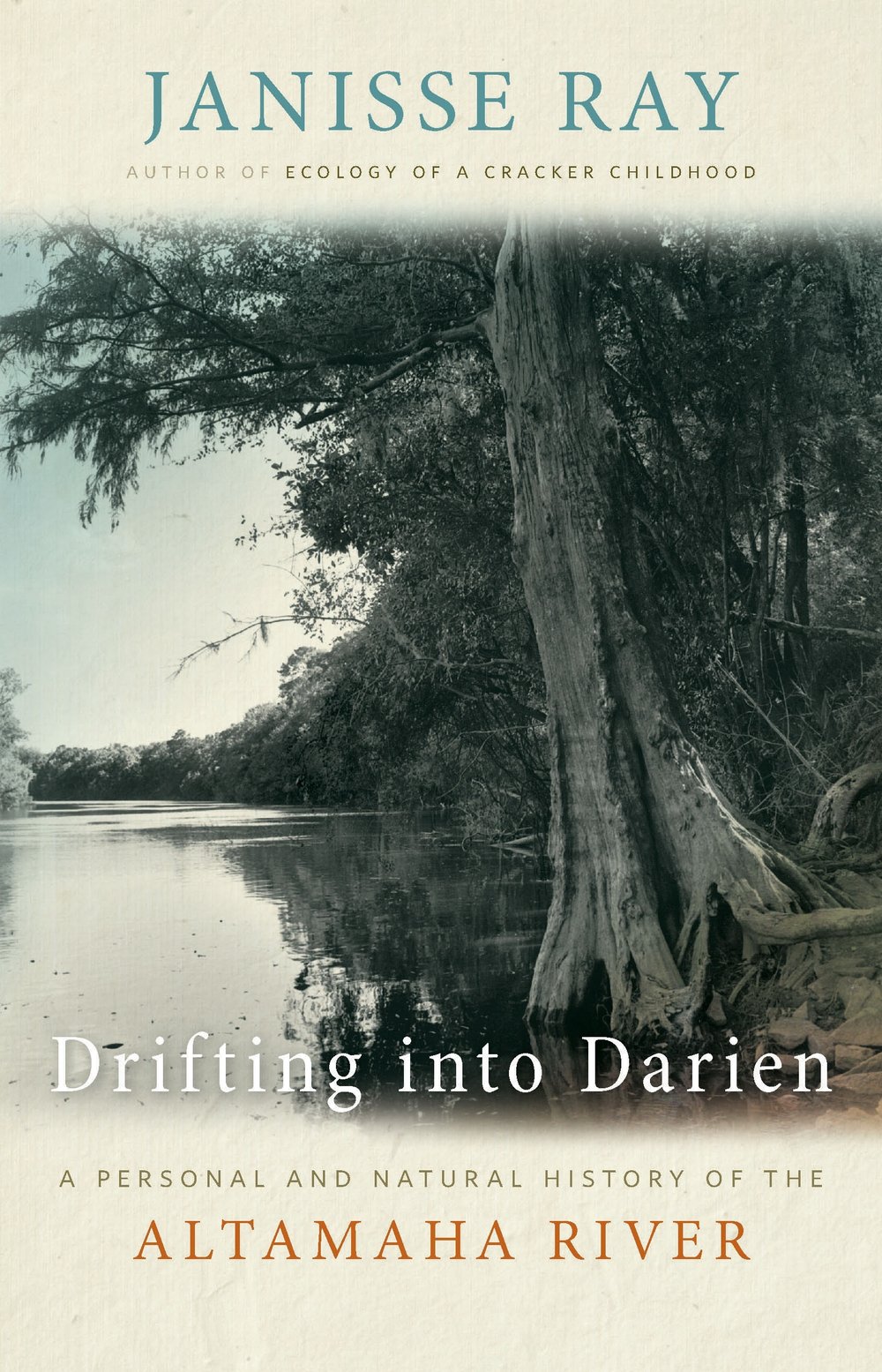

Janisse Ray claims the Altamaha river in her work Drifting Into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River and she has every right to this little-known river: she grew up alongside the river, it’s in her blood and she lives there now. The first section of the book is a wonderful narrative of an 11-day kayak down the river with a group of friends and her husband—they have recently married, so there’s a twinge of honeymoon there as they escape the “real world.” There are delicious descriptions of birds, and the best description of paddling at night (one of my favorite things to do): “A river at night is magic. The feeling is of weightlessness, of floating not just horizontally but also vertically. Humans own the daylight, animals own night. A night paddle is about breaking biorhythms. It’s about becoming animal.” Yes. The second half of the book includes essays about the river: forming the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for instance. There’s a chapter on fresh water mussels and one on the absence of bears; there are sturgeon and fishing trips and politics. And, there’s grief, loss that informs some of these essays but mostly love—for the river, for the creatures, for life.

Janisse Ray claims the Altamaha river in her work Drifting Into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River and she has every right to this little-known river: she grew up alongside the river, it’s in her blood and she lives there now. The first section of the book is a wonderful narrative of an 11-day kayak down the river with a group of friends and her husband—they have recently married, so there’s a twinge of honeymoon there as they escape the “real world.” There are delicious descriptions of birds, and the best description of paddling at night (one of my favorite things to do): “A river at night is magic. The feeling is of weightlessness, of floating not just horizontally but also vertically. Humans own the daylight, animals own night. A night paddle is about breaking biorhythms. It’s about becoming animal.” Yes. The second half of the book includes essays about the river: forming the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for instance. There’s a chapter on fresh water mussels and one on the absence of bears; there are sturgeon and fishing trips and politics. And, there’s grief, loss that informs some of these essays but mostly love—for the river, for the creatures, for life.

Mike Freeman paddled the length of the Hudson in a canoe and wrote about it in his narrative, Drifting: Two Weeks on the Hudson. He started as near to the headwaters in the Adirondacks as he could (the river emerges at Lake Tear of the Clouds near the summit of Mt. Marcy) and made his way south portaging, running rapids and once flipping over (a wonderfully dramatic moment). Amidst tales of eating more power bars than anyone should consume are lots of ideas on the environment, economy (Freeman was hit hard by the recent recession), politics, and religion (one of my favorite lines: “If there’s one thing I’ve always admired about churches, they were places people went to feel absolutely horrible about themselves.” ) The river, then, is a vehicle for ideas. Unlike me (and several of the other writers here), Freeman isn’t trying to claim the river as his in any way; he is just visiting (recently moved east from Alaska) for two weeks, to see what he could see and let his ideas wander with the river. Freeman is not an easy-going drifter—he’s on a fast course down the river, and his rants against everyone from polluters to coffee drinkers have the same sort of urgency.

John Lane, a prolific southern writer, took to the stream in his backyard in South Carolina and canoed to the sea via the Broad, Congaree and Santee Rivers. His tale: My Paddle to the Sea: Eleven Days on the River of the Carolinas is framed by a river accident in Costa Rica in which one of the guides and one paddler drown. There are two choices in the face of such a heart-breaking event: never paddle again, or paddle into your sadness and fear. Lane chose the latter. His narrative, then, is rich in thoughtfulness with depth. At the heart of it are two friendships, first with the larger-than-life character with whom he paddles the first eight days of his journey, Venable Vermont (by name alone he takes wonderful space in the book) and the his neighbor Steve Patton. Through the trip Lane confronts more rain than any person should have to weather. Though there’s a tension at the end—will he and Steve Patton make it to the ocean—there’s a wonderful easy-going feel to this story, and Lane is a great companion, a wilderness lover, “More John Muir than Teddy Roosevelt.” (Venable is a good antidote to Lane’s dreaming). There’s a lot of terrific, southern history, literary history, river’s history in this book. I came away smarter for it.

John Lane, a prolific southern writer, took to the stream in his backyard in South Carolina and canoed to the sea via the Broad, Congaree and Santee Rivers. His tale: My Paddle to the Sea: Eleven Days on the River of the Carolinas is framed by a river accident in Costa Rica in which one of the guides and one paddler drown. There are two choices in the face of such a heart-breaking event: never paddle again, or paddle into your sadness and fear. Lane chose the latter. His narrative, then, is rich in thoughtfulness with depth. At the heart of it are two friendships, first with the larger-than-life character with whom he paddles the first eight days of his journey, Venable Vermont (by name alone he takes wonderful space in the book) and the his neighbor Steve Patton. Through the trip Lane confronts more rain than any person should have to weather. Though there’s a tension at the end—will he and Steve Patton make it to the ocean—there’s a wonderful easy-going feel to this story, and Lane is a great companion, a wilderness lover, “More John Muir than Teddy Roosevelt.” (Venable is a good antidote to Lane’s dreaming). There’s a lot of terrific, southern history, literary history, river’s history in this book. I came away smarter for it.

I would say that all of these books have an environmental agenda, but the most explicit is in David Gessner’s My Green Manifesto: Down the Charles River in Pursuit of a New Environmentalism. It has the outrage of a manifesto—outrage, interestingly enough, against environmentalists (in particular he slays two: Shellenberger and Nordhaus, who wrote “The Death of Environmentalism”) whom he sees as nagging and who repeat “global warming” too frequently. Which means that Gessner has a sense of humor, a rare quality in environmental writing. What I appreciated most is that birds are his “soft spot.” And it is through birds, through watching birds (though not being a birder!) that we really observe, and in observing we “migrate outward.” This looking outward is the first “step toward falling in love.” And it is when we love something, someone, a bird or a place that we want to protect it. So Gessner’s manifesto is really a return to caring for what we know, for where we live. This gives new life to the NIMBY environmentalist (which is what I am and have continued to preach for in these days of global warming). The journey down the Charles is conversational, even casual and is filled with beer and jokes and nearly breaking the canoe in half—in this sense it will appeal to a young audience. And that is exactly who Gessner wants to get with his book; he wants to light a fire under those young butts. So it is a manifesto indeed.

My Reach in the World

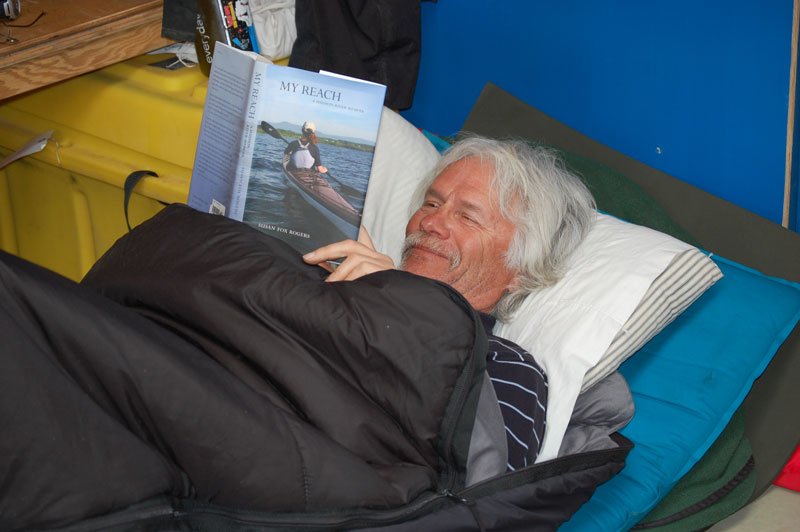

As My Reach sails into the world friends have been sending photos of them reading--or not reading. Here are a few. Send me more photos!

Lisa Sanditz on the Jersey Shore

David Ainely, Penguin expert, reading in Antarctica!

Tim Davis, enthralled!

Lisa Sanditz, Colorado

Indian Point

From water level, the towers loomed above me and the entire structure felt imposing. There are layers of red brick buildings smack against the river. Not a window in sight, as if whatever was contained inside shouldn’t be seen, and should not see out. I’d passed some large industry on the river—Trapp Rock up by Poughkeepsie, for instance, but nothing that felt ominous like the Indian Point plant. There are many reasons to protest nuclear power. In my life, the stories of Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima are enough to convince anyone this is a risky source of energy. There are many reasons not to want a nuclear power plant so close to a major metropolitan area—9/11 is enough to show how vulnerable we can be. And there are many reasons not to want a nuclear power plant on the Hudson River. The plant rests on a small earthquake fault. And, the plant uses billions of gallons of water t o cool its towers and then spits this warmed water back into the river, altering the ecosystem. In the process, millions of fish are sucked into the plant and killed. But I had not thought about any of this with much care until I stroked past the plant low in my boat.

One spring, I loaded up my kayak with sleeping bag and food and pointed south on the Hudson River. I was traveling with a former student, Emmet, and we intended to take a few days, camping on islands and on the banks of the river, to make our way from my village of Tivoli to Manhattan (I write about this adventure in my upcoming book, MY REACH). This is the freedom of a river, to head out and see what you can see. And I did see many marvelous things on my journey, and lots that I wish I had not seen. Day four I passed the Indian Point nuclear power plant. Instinctively, we scooted to the western shore, giving the plant a wide berth.

From water level, the towers loomed above me and the entire structure felt imposing. There are layers of red brick buildings smack against the river. Not a window in sight, as if whatever was contained inside shouldn’t be seen, and should not see out. I’d passed some large industry on the river—Trapp Rock up by Poughkeepsie, for instance, but nothing that felt ominous like the Indian Point plant. There are many reasons to protest nuclear power. In my life, the stories of Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima are enough to convince anyone this is a risky source of energy. There are many reasons not to want a nuclear power plant so close to a major metropolitan area—9/11 is enough to show how vulnerable we can be. And there are many reasons not to want a nuclear power plant on the Hudson River. The plant rests on a small earthquake fault. And, the plant uses billions of gallons of water t o cool its towers and then spits this warmed water back into the river, altering the ecosystem. In the process, millions of fish are sucked into the plant and killed. But I had not thought about any of this with much care until I stroked past the plant low in my boat.

Floating in a kayak on a big river I often feel tiny, especially next to tankers or the barges that shove north and south at all times of day and night (in this photo, a tanker is emerging around Magdalen Island--that little dot is me). But my river view is an important perspective, it’s the same view a beaver might have, or a great blue heron wading by the shoreline. In a kayak, there is an intimacy with the water, whether that water is clean or not, the sights beautiful or not. And I did not like being intimate with a nuclear power plant. It took experiencing the chill of Indian Point on a cool rainy spring day to make me care about shutting down the plant.

And so it comes as good news that Governor Cuomo wants to shut down Indian Point and that new legislation will make this possible. This long battle may finally come to an end. According to Times reporters, Entergy, the company that runs the plant, came away from the meetings “alarmed” with the governor’s direct and strong intentions.

Even though I am skeptical that Indian Point will be shut down, I’m going to be naïve and pretend this is true. I have decided to begin my celebration by wondering what happens to a closed nuclear power plant. Will it join the history of closed industry along the river? When I paddle the length of the estuary, I have passed brick towers that are the remains of the icehouses (photo at left) that stored and brought ice to keep Manhattan cool. There are the sheds that were used in brick making just north of Kingston where teenagers now come to skateboard, the clatter of their leaps and landings echoing through the tall, metal-roofed buildings. There are the remains of the cement industry, and an enormous brick building near the water in Germantown that says “Cold Storage.” These ghosts of industry past I find intriguing, often beautiful. I slip onto shore and out of my boat and poke around these structures, wary of broken glass and often taking a brick as a souvenir. Manhattan is built from Hudson Valley cement and brick. In an odd nostalgia, I wish that this industry were still alive, but cement is reduced to three plants near Smith’s Landing, and the brick industry closed for good in 2001. Yet the end of these industries means a cleaner river, a quieter, calmer river for me to paddle on. One hundred years ago, would I have wanted to see the brick industry close?

So in a hundred years will someone paddle past the crumbling towers of Indian Point and wonder about nuclear power? Perhaps there will be a certain nostalgia as she wishes that we still had that plant generating electricity for New York City. Or will she wonder what we ever imagined was good or sane about nuclear energy?