My Reach

As I slid my kayak into the Hudson River last Wednesday evening, the water grabbed my ankles. My calf muscles seized with the cold. I tuc

A reach is a stretch of navigable river, often the distance the eye can scan. On the Hudson there are a range of reaches, most with direct names like the Barrytown Reach or the North Germantown Reach. Some have names that have existed since when Henry Hudson sailed up the river in 1609 like the Long Reach off of Poughkeepsie. When Ed Abbey claims the desert in Desert Solitaire as his own, “Abbey Land,” it is because he is the only one there and because he loves it. I too make my claim out of love, but I can’t claim I am the only one on the river. I share my reach with many—many who no doubt imagine that this is their reach as well.

As I slid my kayak into the Hudson River last Wednesday evening, the water grabbed my ankles. My calf muscles seized with the cold. I tuc ked into my boat and settled into the seat of my kayak. I then strapped the sprayskirt tight, before dipping my paddle into the spring-brown water. This was my first time in my kayak on the river this season, a late start for many reasons, but mainly due to our over-rainy spring. I was eager to scout about the section of river off of Tivoli that I think of as my reach.

A reach is a stretch of navigable river, often the distance the eye can scan. On the Hudson there are a range of reaches, most with direct names like the Barrytown Reach or the North Germantown Reach. Some have names that have existed since when Henry Hudson sailed up the river in 1609 like the Long Reach off of Poughkeepsie. When Ed Abbey claims the desert in Desert Solitaire as his own, “Abbey Land,” it is because he is the only one there and because he loves it. I too make my claim out of love, but I can’t claim I am the only one on the river. I share my reach with many—many who no doubt imagine that this is their reach as well.

Because I see this as my reach, when I paddle about I note changes, good and bad: new graffiti on the abandoned dock; the for sale sign down on the blue-roofed house at the end of the jetty (who gets to live there?!); more debris like sticks and logs in the water from all of the rain. And because I call it mine, I pick up the plastic water bottle bobbing in the water, and wonder how the herring run was this year.

The Saugerties Lighthouse pulled me north and across the river. I scanned for boats as I crossed the choppy channel mid-river. Motor boats were out on this rare clear day, but I did not spy any barges or tankers. At the lighthouse, I slid onto the sandy beach on the north side, and pulled out of my boat. In just a short time—the half hour it took me to cross—my lower back already had a pleasant tightness. As I wandered the beach and onto the path that leads from land to the lighthouse it sounded like I was at a baseball game as several Baltimore Orioles gave off their exuberant calls. And then overhead I spied a large flock of small geese, silent in their journey north. Brant. Brant are a small goose that nests in the arctic. These birds had come a distance, anywhere from Georgia to the New Jersey coastline, and had a long distance in front of them.

There were about fifty Brant in that first flock. But just minutes behind them was another flock, their messy V shape dotting the blue sky. Over 250 birds had gathered for their annual pilgrimage. I walked back to my boat, pushed off and cruised south with the outgoing tide. I needed to make a full sweep of my reach, down to Magdalen Island, with a quick dip into the North Tivoli Bay.

As I paddled south, one flock of brant after another crossed overhead ranging in size from eight, cruising low to the water, to flocks of several hundred, higher in the sky. I wondered if they used the river to navigate, to find their way from Georgia to the far north.

A fisherman idled in the river in a flat bottomed boat. As I neared I saw his line tighten. I watched as he pulled up, the rod arcing with the strain. Then he lowered his rod, reeling in the line. Pull, reel, pull, reel. It took a good ten minutes to get the fish up. And as soon as it was in his boat, he had it unhooked and had dropped it back in the water. I watched the fish—a good foot and a half long—as the fisherman slid it into the water.

At Magdalen Island I crossed back to the eastern shore of the river. Cutting in close to the island, I smelled a rich mixture of earth and honeysuckle. The fluky waters at the southern end of the island tossed me about as I rounded the island to dip into the North Tivoli Bay. An osprey swooped overhead and perched on the north end of the island. Just a dozen yards from the big raptor perched three great blue heron, perhaps settling into the trees for the night.

The water pushed me under the railroad trestle and into the bay. The late evening light added a glow to the quiet bay where the cattails and phragmites have yet to start their spring growth. The bay looked barren, but the bird calls let me know that life was alive and well. From the stubby reeds of last year I heard swamp sparrows, marsh wrens, and the ever-present red-winged black birds. And then from inland emerged the distinctive tap-tapping call of the Virginia Rail. From the other side the rail was serenaded by another rail, cack-cacking in response. Grinning, I turned back to the big river, wanting to get back to Tivoli before nightfall as I had forgotten my light.

As I approached the underpass I saw that the water was running faster than usual; the rain swollen river was making the outgoing tide more vigorous. I tightened my life vest, felt happy my binoculars are waterproof, made sure the toggle on my sprayskirt was easily accessible. If I went over, I would tug on it, and drop out of my boat. In other words, I headed for the underpass expecting to go over. I’m not sure why I expected the worst, since in ten years of paddling the Hudson I have yet to dump out of my boat. But the waters felt tricky.

I took a running start, picking up speed as I headed toward the steel girders that support the trains that rush by overhead. I aimed for the southern end of the underpass, knowing the water would push me north. Fueled with adrenalin, I shoveled the water. Then I had to bend over to pass under the girders. This gave me less leverage. Not so slowly, I was being pushed toward the cement supporting wall. I adjusted my boat, paddled, adjusted and finally slammed into the cement wall. I waited for the water to suck me under but instead, I held the wall as the water rushed past. I pushed off from the wall and gave the last ten feet my best effort. When the nose of my boat emerged from under the bridge, the waters instantly calmed. I stroked a few feet toward Magdalen Island, sat back in my seat and breathed deeply. I did not go over, I felt lucky.

The herons sat placid in their trees, unaware of my adrenalin-inducing moment exiting the North Bay. The sun dipped behind the Catskill Mountains adding a glow to the sky. Two more flocks of brant cruised silently overhead. The sun set--another gorgeous sunset--over the Catskill Mountains.

Two young men were standing at the landing when I pulled up. One helped me put my boat on my car. They were graduating Bard College students, one a dancer, the other a history major. I told the dancer he shouldn’t smoke as he puffed on a cigarette. “I’ve been smoking longer than I’ve been dancing,” he said with a smile. I wanted to tell him he should have taken a course in basic logic.

They asked what I had seen. Many wonderful things. “Brant,” I told them. “Sixteen flocks.” I wasn’t convinced they were interested, but I had to tell them of the brant’s remarkable journey north.

“What’s that?” the dancer asked pointing across the river.

More brant. Seventeen flocks of the arctic-bound geese.

Spring Cleaning

Lucky for me, the town of Red Hook holds an annual clean up day. On Saturday, fifty people took to the local roads with gloves and large black plastic bags to collect bottles and whatever else people enjoy tossing by the side of the road. Through the winter, all of this debris is hidden. When the snow melts, all of our carelessness is revealed.

My road to clean was Sengstack Lane, at the north end of my home in the village Tivoli. I cleaned this section of road last year and ended up with two tires and six bags of junk. This year, I only needed but two bags. Is it possible that less litter was left behind? Or was it simply that last year’s effort took in several years of debris? (This clean up has been in place since 2009 so this is possible.)

Sengstack is part of my morning walk. When I reach this stretch of road, the sky opens up with a large, empty horse farm to the north and the Catskills on the western horizon. A harrier often works the field, and I watch him as he cruises just above the tall grass line scanning for prey. On this day I was serenaded by a flicker’s call, a field sparrow in the phragmites patch, and an insistent cardinal. I wore a wide-brimmed hat in the afternoon sun, and carried my garbage pick up stick to reach into the bushes, grab bottles and cans.

Picking up garbage can be a social event, or when alone, deeply meditative. It was quiet along the road; a few cyclist out for a ride in the warm spring air waved as they passed. Other than that it was me, my bag of garbage (that started to stink), and the wide sky. I thought of nothing and everything. I solved no world problems or personal problems. I just enjoyed the small but real satisfaction of making these few miles of road tidy.

Spring cleaning is an urge that runs deep: some people clean the blinds, wash the floor, throw out clothes. Some dig weeds, rake winter debris in the garden, and some, like me, want to clean the earth. April 30 & 31 was officially garbage weekend.

Lucky for me, the town of Red Hook holds an annual clean up day. On Saturday, fifty people took to the local roads with gloves and large black plastic bags to collect bottles and whatever else people enjoy tossing by the side of the road. Through the winter, all of this debris is hidden. When the snow melts, all of our carelessness is revealed.

My road to clean was Sengstack Lane, at the north end of my home in the village Tivoli. I cleaned this section of road last year and ended up with two tires and six bags of junk. This year, I only needed but two bags. Is it possible that less litter was left behind? Or was it simply that last year’s effort took in several years of debris? (This clean up has been in place since 2009 so this is possible.)

Sengstack is part of my morning walk. When I reach this stretch of road, the sky opens up with a large, empty horse farm to the north and the Catskills on the western horizon. A harrier often works the field, and I watch him as he cruises just above the tall grass line scanning for prey. On this day I was serenaded by a flicker’s call, a field sparrow in the phragmites patch, and an insistent cardinal. I wore a wide-brimmed hat in the afternoon sun, and carried my garbage pick up stick to reach into the bushes, grab bottles and cans.

Picking up garbage can be a social event, or when alone, deeply meditative. It was quiet along the road; a few cyclist out for a ride in the warm spring air waved as they passed. Other than that it was me, my bag of garbage (that started to stink), and the wide sky. I thought of nothing and everything. I solved no world problems or personal problems. I just enjoyed the small but real satisfaction of making these few miles of road tidy.

The next day, one of my students in my nature writing class at Bard College, Gleb Mikhalev organized a few students to clean up the Tivoli Bays. The Bays are my paddling ground, two wide scoops of shallow water rich in birds and snapping turtles and beavers. The bays are separated from the Hudson River by the train tracks. For each bay, two underpasses allow the water to come and go with the tides, depositing trash but rarely taking it away with the outgoing current. So the bays are often rich in garbage as well.

Cleaning up the bays is something I’ve done for four years and it’s always an event, a great treasure hunt in the high tide line. Six students showed up, looking like they’d tumbled out of bed fifteen minutes earlier. We organized canoes, and all headed off, the students in a line to the south end of the bay. I didn’t see them again for the rest of the day.

In my canoe at the rudder was Max Kenner, a Bard graduate now running our successful prison program. He was the perfect, optimistic companion. As we scooted under the train trestle and onto the wide river, he glowed with the fun of it under a perfect, sunny sky. He reminded me that this was less about garbage and more about being on this beautiful river in the spring.

In the distance, the Catskills loomed brown from the winter, with a ruff of green at the base. We curved around the end of Cruger Island and followed the choppy water’s north to land at a cove on the north end. This cove is the perfect spot to picnic, or camp (though that is not legal). There’s a log ideal for sitting and eating sandwiches (which we did). Then we picked up two bags of stuff left by campers.

I picked up a pull tab—the tabs that used to seal soda cans. As a kid, I remember hooking my index finger through the tab and pulling it off. I would then slip the tab into the can where it would float around as I drank my soda. This is the sort of thing you think about cleaning up garbage: when was this invented and by whom? (1956 by Mikola Kondakow invented them for bottles and then later in1962, Ermal Cleon Fraze invented the tab with the ring that would come off completely.) And why did we stop using these pull tabs? (in the 80s the stay on tab was invented to REDUCE ROADSIDE GARBAGE! And to reduce injuries—some people swallowed the floating tabs). (All answers are from Wikipedia, of course)

Satisfied with our clean up, we continued north, where we gathered up an enormous Styrofoam block that straddled the canoe, as well as a long metal rod, a cooler and a plastic chair. Once in the Tivoli north bay, we slowed our pace, grabbing a bottle here and there as we discussed life, relationships and how great it was that the swamp sparrow and the marsh wren were singing amidst the noisier red-winged blackbirds.

My former student Aaron Ahlstrom met us at the dock in the north bay and I swapped out companions. Aaron is tall and lanky, a runner now launched into a career in historic preservation. Max departed with the load of garbage we had collected, and Aaron joined me, infusing me with new energy. Spotting garbage—the glint of glass or plastic tucked into the dry stalks of cattails or phragmites—is an art that requires patience and a keen eye. Finding a hunk of garbage is satisfying, even though I did not want to see that bottle lying in the muck. I felt a surge at each find. This drive—the hunt one of our most essential drives—is often sated with a gun. But binoculars or a garbage pick up stick work just as well.

As we clambered out of the canoe to gather bottles, tromping into mud and into the reeds, I flushed two Virginia rail and one Least Bittern. The birds took off, their secretive lives momentarily disturbed.

By six in the evening we were back in the tranquil south bay with an impressive load of stuff headed for the Bard College dump (thank you Bard B&G for hauling everything away). I was dirty and tired and completely satisfied. I saw the load of trash collected by the students, their boats already secured. “It’s your duty to keep American beautiful,” an advertisement from the 70s, echoed in my head. These students are given other environmental messages (drive a Prius! Recycle! Eat local! Despair over global warming!), but for this one long sunny day they were learning this message of local stewardship. They had helped to make what is beautiful that much more lovely. And it brought them all into coves and through reeds, giving them an intimacy with a place that for four years they call home. I called Gleb to see how their day had unfolded. “We had a great time,” he said. A great time gathering garbage. That gives me hope.

Back on the Water

I settled into my kayak, pushing my back into the seat and my knees up into the side of the boat. I tugged the spray skirt into place, and took my first stroke, my hands adjusting to the paddle. As I glided forward, mute swans flew overhead, the whoosh of their enormous wings like someone bowing the air. This was perhaps the only time of year it is possible to paddle into the Vly as in summer the surface is covered by floating mats of vegetation. But in early spring a wide shallow channel marked the middle of the marsh.

I write back on the water and not on the river because this first paddle of the season was on a freshwater marsh, named the The Great Vly in Ulster County. The weather was warm, the sun out, and the wind blowing—a perfect northeast spring day. The Vly is about a mile long, choked with phragmites, and cattails. Short cliffs and woods rim the Vly on the western side and low hills cradle the eastern side. The tail end of a cement factory is visible at the far northeastern end (Lehigh Cement runs from the Vly to the Hudson River).

I settled into my kayak, pushing my back into the seat and my knees up into the side of the boat. I tugged the spray skirt into place, and took my first stroke, my hands adjusting to the paddle. As I glided forward, mute swans flew overhead, the whoosh of their enormous wings like someone bowing the air. This was perhaps the only time of year it is possible to paddle into the Vly as in summer the surface is covered by floating mats of vegetation. But in early spring a wide shallow channel marked the middle of the marsh.

Peter was ahead of me in his green kayak, his camera cradled between his legs. We passed Canada geese nesting in clumps of grasses, and a few beaver lodge, the sticks piling high like water-based teepees. Ring-necked ducks, mallards and a few teal rose when we got within two hundred yards (ducks are skittish!). At the northern end of the Vly, I followed a narrow path into the grasses. I couldn’t see Peter or the birds. I knew that but a mile or so away in one direction ran the New York State Thruway, and in the other sat the cement plant. But there in the marsh was a sense of still isolation, just a drop of land protected from the rush of the world.

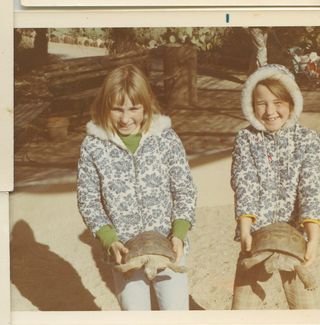

As I paddled about I kept thinking: this smell is familiar. And then it came to me. The Vly smells like my sister’s turtle tanks from when we were children. Inside those tanks was a mixture of algae, turtle poop and then the turtles themselves, a cast of soft shell turtles and painted turtles that lived short but loved lives.

The tanks always needed more cleaning. Every so often, when the water became unhealthily murky, Becky would stick a clear plastic tube into the tank and siphon out most of the water. To get the water flowing, she would fill the tube with water, plug both ends, and if all went well, when she released her thumbs, the water would flow. Often, it did not, so she resorted the most assured way: sucking on the end of the tube. Only she didn’t like sucking on the tube. So she would call in her little sister. “Help me out,” she would coax. And I would. The first time I ended up with a mouthful of turtle tank water. Later, I would watch the cloudy water zooming down the tube toward my mouth and let go just before it arrived. But there I would be, hovering over a plastic bucket of turtle water, inhaling the smell of turtle life.

So there I was, paddling in a large body of turtle water. Which means there had to be turtles.

“I’ve seen five,” Peter said, which didn’t surprise me. Peter sees and hears everything in the woods and streams—the mink by the side of the pond, the grouse drumming in the woods, a thumping beat I would easily miss.

I had seen none. But truth was I hadn’t been looking for turtles, I’d been looking at the eagles soaring overhead, and hoping to see a goshawk as well.

I scanned the shoreline. Peter told me to look on logs, and on the beaver lodges. Turtles like to sun. “Look for something shiny,” Peter said. “And if you are lucky, maybe we’ll see a yellow spotted turtle.” He paused. “They are pretty rare.”

The yellow spotted turtle is on the endangered list in Canada, and though it’s not on that list in this country, it is “vulnerable to extinction in the wild.”

I wanted to see one. What is this urge to see the rare, the species poised to disappear, perhaps in my lifetime? This wasn’t the first time. I’ve made long detours in hopes of seeing a whooping crane, and I’ve tromped through miles of sagebrush to see a greater sage grouse. It is Peter’s stories of when he set afloat in the waters of Arkansas looking for the Lord God Bird—the Ivory billed Woodpecker—that thrill me the most. Somewhere in my thinking is that seeing these creatures means they are still here with us, that things are not as dire as I fear. But beyond this need to be reassured is something else more primitive: seeing them—when I am that fortunate--is special. It’s like being awarded that grant or residency, which always feels like half work, half (or more) chance. Or, it’s like finding that one perfect partner—amongst the several billion on this planet--to venture out with onto a marsh on a spring day.

I suppose my urge to see the rare isn’t unlike someone who flies to Paris to see the Mona Lisa or to Rome to see the Sistine Chapel. But to see these treasures simply requires determination, paying a fee (and usually standing in a long line). And it’s possible to return again and again to see these rarities. To see the turtle would require stealth, a keen eye, and good luck.

We approached the shore where we had put in two hours earlier. My lower back could feel the tender ache of this first paddle. I felt happy, even though I had given up on the goshawk, and had resigned myself to no turtle.

“There,” Peter said, as we neared the shore.

And there they were, two spotted turtles, sunning on a log. We watched them for ten minutes before they slid off the log into the turtle water.

Snake Bight Trail

Snake Bight Trail

Just that morning we had packed up our tent in the Pine Key Campground in Everglades National Park where through the night we listened to the chuck will’s widow sing its eponymous song. We had spent the past three days in the park, walking trails and spotting an amazing range of birds: mangrove cuckoo, anhinga, shiny cowbird, purple gallinule, and limpkin. Overhead, against a light blue sky we spied snail kite, short tailed hawk, swallow-tailed kite, and many osprey carrying food to their nests. Despite this bounty of birds, we still wanted to see one pink creature: the greater flamingo. To see one, we had to walk the 1.7 miles out the Snake Bight trail.

It’s Friday morning and Peter and I are walking around the parking lot of a Burger King in Homestead, Florida. It’s already 80 degrees, and the heat clings to my skin, while grease works it way up my nostrils. This might be the rudest reentry to civilization I have ever experienced in my camping/outdoor life. Reentry is always hard—the sounds and smells too much, the whir of traffic too insistent. But we’re looking for a myna bird, a big billed black bird that obligingly lurks near the dumpster. So fast we are back in our air-conditioned rental car.

Just that morning we had packed up our tent in the Pine Key Campground in Everglades National Park where through the night we listened to the chuck will’s widow sing its eponymous song. We had spent the past three days in the park, walking trails and spotting an amazing range of birds: mangrove cuckoo, anhinga, shiny cowbird, purple gallinule, and limpkin. Overhead, against a light blue sky we spied snail kite, short tailed hawk, swallow-tailed kite, and many osprey carrying food to their nests. Despite this bounty of birds, we still wanted to see one pink creature: the greater flamingo. To see one, we had to walk the 1.7 miles out the Snake Bight trail.

Snake Bight is a flat path (as all the paths are in the Everglades) that leads from the road to a bight, or a bay within a bay (hence the name—you do not get bitten by snakes on the path, though if you are lucky you get to see a snake). Walking this path is a birder’s pilgrimage: every birder who wants to add the flamingo to his or her ABA-area life list has stepped here. I wondered at the hundreds of determined, expectant feet that had stepped here before us (if you have walked Snake Bight and have a story you would like to share, please email me! susan@susanfoxrogers.com).

Most of the path is shaded by mangrove trees, though at noon nothing keeps the sun from blaring down through the small, shiny green leaves. The trail is rimmed by a riot of brush, an occasional red cardinal flower, an occasional prickly pear cactus. Fifteen feet into the brush a murky narrow waterway parallels the trail: perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. And yet the path had a spirit-buoying sweet smell from decaying leaves. Though it was spring in Florida, it smelled like fall in the Northeast, my favorite season.

At the end of the path a boardwalk stretches into the bay where we looked out onto low tide and in the distance hundreds, perhaps thousands, of wading birds. Was there a flamingo among them? No doubt. But even with a scope we would not know. So we walked back, slapping mosquitoes and regretting we had not brought food or water.

When we arrived at our car, we heard branches breaking and a crash as something emerged from the brush. An alligator, eight feet long, long-legged its way onto the strip of short grass near our car and but a dozen feet in front of us. It made a low, guttural hiss. We stepped back. It settled, melting like pudding into the grass, and assumed its napping position.

We were determined to visit Snake Bight at high tide, which would bring the birds in closer. At high tide, the water is a foot, at times two feet deep—perfect for long-legged wading birds. So we got up the next morning, made a brief loop of the Eco Pond, where we saw roseate spoonbills in all of their pink glory, along with white ibis, wood storks, and stilts. Then we made the walk a second time, now in the relative cool of morning. High tide brought the birds a bit closer, but there were fewer birds. We stood, slightly disappointed, watching birds sail through the sky and calling out, “Pink one, heading right.” Pause. “Roseate.” “Pink one, flying left,” I called. “Does it have black on its wings?” I thought I saw those bold lines. “Which one?” Peter asked. Which one? The sky was an infinite blue, the birds an infinite traffic of dots.

Fifteen minutes passed. We entertained ourselves with an immature ibis near shore and attempted to walk out on the marsh so we could be nearer to where the birds clustered (guidebooks warn that people sink, and “disappear”!).

“You know what this smells like?” Peter observed, “when you boil a deer’s head.”

“No kidding,” I said.

He knew he had to explain more. “To get the antlers, from road kill, that’s what I did.”

As a child, Peter hunted. He has long since put down his gun and picked up binoculars but all of those skills of a hunter translate. He sees and hears birds, but he also sees the mink by the side of the pond, a ripple that is a beaver, the coyote slinking through the woods, and the smell of the fox. And, he knows what it smells like to boil a deer’s head.

We were just at the point of giving up on the flamingo when we heard a grinding cackle that is unmistakable: rail. And there was the skinny, secretive bird, scurrying from one tuft of grass to another. And then it had a cousin on the mainland hollering back, and suddenly we had a rail fest, me giddy and Peter snapping photos so he could later piece together if these were King Rail or Clapper Rail.

And it would be good if this story ended with a flamingo winging its way overhead. But birding, like life, is not always so neat. And birding, like life, is most fun when you go looking for a flamingo and instead meet an alligator or hear the cackle of a King Rail.

Photos of pelican, little blue heron and ibis are taken by Peter Schoenberger.