Paddling in Good Company

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Mid-way through the fall I learned that mine was not the only book to be published this season about paddling down a river. Four other books carried writers into print this fall, from the Charles River in Massachusetts, to the rivers of the Carolinas, to the Altamaha in Georgia. I love these sorts of convergence. Certainly there are many paddle down river books but why five in one season? What has drawn us all to float and think—about rivers, about the environment, about life. Because if one thing unites these books is thinking about the world—paddling, whether in a canoe or a kayak, invites reflection. What is intriguing are the ways these books overlap, observations echo (those great blue heron; those sturgeon), words repeat ("drifting" "My") and number of pages to tell the story align (221 it is!). In some ways, this could be because a river is a river (though this isn’t exactly true) and paddling is paddling (again not true) but it seems we all turned to rivers for ideas, solace, inspiration, love. Rivers formed this country, and if I can conclude one thing it is that being in and on a river shapes how we see the world, relate to the world. I want to say they made us better people, though that sounds really cheesy. What I mean by better is more aware of our own thoughts, biases and desires, more attentive to the world, more appreciative of life. I’ll stop there before I write something foolish like: paddling is good for the world, not just for the soul.

Over this break, I’ve read the books of my four river companions. Here are some observations.

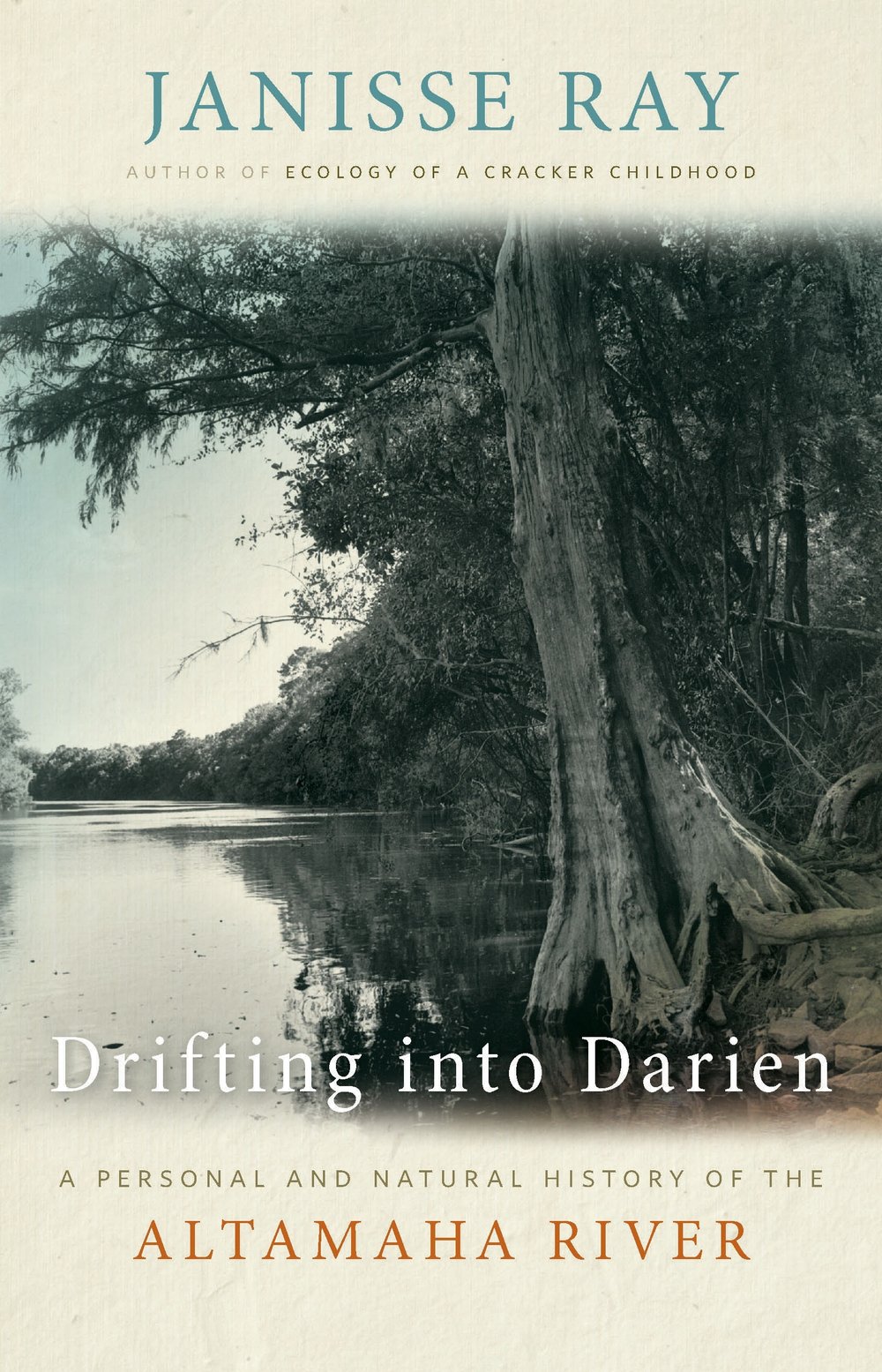

Janisse Ray claims the Altamaha river in her work Drifting Into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River and she has every right to this little-known river: she grew up alongside the river, it’s in her blood and she lives there now. The first section of the book is a wonderful narrative of an 11-day kayak down the river with a group of friends and her husband—they have recently married, so there’s a twinge of honeymoon there as they escape the “real world.” There are delicious descriptions of birds, and the best description of paddling at night (one of my favorite things to do): “A river at night is magic. The feeling is of weightlessness, of floating not just horizontally but also vertically. Humans own the daylight, animals own night. A night paddle is about breaking biorhythms. It’s about becoming animal.” Yes. The second half of the book includes essays about the river: forming the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for instance. There’s a chapter on fresh water mussels and one on the absence of bears; there are sturgeon and fishing trips and politics. And, there’s grief, loss that informs some of these essays but mostly love—for the river, for the creatures, for life.

Janisse Ray claims the Altamaha river in her work Drifting Into Darien: A Personal and Natural History of the Altamaha River and she has every right to this little-known river: she grew up alongside the river, it’s in her blood and she lives there now. The first section of the book is a wonderful narrative of an 11-day kayak down the river with a group of friends and her husband—they have recently married, so there’s a twinge of honeymoon there as they escape the “real world.” There are delicious descriptions of birds, and the best description of paddling at night (one of my favorite things to do): “A river at night is magic. The feeling is of weightlessness, of floating not just horizontally but also vertically. Humans own the daylight, animals own night. A night paddle is about breaking biorhythms. It’s about becoming animal.” Yes. The second half of the book includes essays about the river: forming the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for instance. There’s a chapter on fresh water mussels and one on the absence of bears; there are sturgeon and fishing trips and politics. And, there’s grief, loss that informs some of these essays but mostly love—for the river, for the creatures, for life.

Mike Freeman paddled the length of the Hudson in a canoe and wrote about it in his narrative, Drifting: Two Weeks on the Hudson. He started as near to the headwaters in the Adirondacks as he could (the river emerges at Lake Tear of the Clouds near the summit of Mt. Marcy) and made his way south portaging, running rapids and once flipping over (a wonderfully dramatic moment). Amidst tales of eating more power bars than anyone should consume are lots of ideas on the environment, economy (Freeman was hit hard by the recent recession), politics, and religion (one of my favorite lines: “If there’s one thing I’ve always admired about churches, they were places people went to feel absolutely horrible about themselves.” ) The river, then, is a vehicle for ideas. Unlike me (and several of the other writers here), Freeman isn’t trying to claim the river as his in any way; he is just visiting (recently moved east from Alaska) for two weeks, to see what he could see and let his ideas wander with the river. Freeman is not an easy-going drifter—he’s on a fast course down the river, and his rants against everyone from polluters to coffee drinkers have the same sort of urgency.

John Lane, a prolific southern writer, took to the stream in his backyard in South Carolina and canoed to the sea via the Broad, Congaree and Santee Rivers. His tale: My Paddle to the Sea: Eleven Days on the River of the Carolinas is framed by a river accident in Costa Rica in which one of the guides and one paddler drown. There are two choices in the face of such a heart-breaking event: never paddle again, or paddle into your sadness and fear. Lane chose the latter. His narrative, then, is rich in thoughtfulness with depth. At the heart of it are two friendships, first with the larger-than-life character with whom he paddles the first eight days of his journey, Venable Vermont (by name alone he takes wonderful space in the book) and the his neighbor Steve Patton. Through the trip Lane confronts more rain than any person should have to weather. Though there’s a tension at the end—will he and Steve Patton make it to the ocean—there’s a wonderful easy-going feel to this story, and Lane is a great companion, a wilderness lover, “More John Muir than Teddy Roosevelt.” (Venable is a good antidote to Lane’s dreaming). There’s a lot of terrific, southern history, literary history, river’s history in this book. I came away smarter for it.

John Lane, a prolific southern writer, took to the stream in his backyard in South Carolina and canoed to the sea via the Broad, Congaree and Santee Rivers. His tale: My Paddle to the Sea: Eleven Days on the River of the Carolinas is framed by a river accident in Costa Rica in which one of the guides and one paddler drown. There are two choices in the face of such a heart-breaking event: never paddle again, or paddle into your sadness and fear. Lane chose the latter. His narrative, then, is rich in thoughtfulness with depth. At the heart of it are two friendships, first with the larger-than-life character with whom he paddles the first eight days of his journey, Venable Vermont (by name alone he takes wonderful space in the book) and the his neighbor Steve Patton. Through the trip Lane confronts more rain than any person should have to weather. Though there’s a tension at the end—will he and Steve Patton make it to the ocean—there’s a wonderful easy-going feel to this story, and Lane is a great companion, a wilderness lover, “More John Muir than Teddy Roosevelt.” (Venable is a good antidote to Lane’s dreaming). There’s a lot of terrific, southern history, literary history, river’s history in this book. I came away smarter for it.

I would say that all of these books have an environmental agenda, but the most explicit is in David Gessner’s My Green Manifesto: Down the Charles River in Pursuit of a New Environmentalism. It has the outrage of a manifesto—outrage, interestingly enough, against environmentalists (in particular he slays two: Shellenberger and Nordhaus, who wrote “The Death of Environmentalism”) whom he sees as nagging and who repeat “global warming” too frequently. Which means that Gessner has a sense of humor, a rare quality in environmental writing. What I appreciated most is that birds are his “soft spot.” And it is through birds, through watching birds (though not being a birder!) that we really observe, and in observing we “migrate outward.” This looking outward is the first “step toward falling in love.” And it is when we love something, someone, a bird or a place that we want to protect it. So Gessner’s manifesto is really a return to caring for what we know, for where we live. This gives new life to the NIMBY environmentalist (which is what I am and have continued to preach for in these days of global warming). The journey down the Charles is conversational, even casual and is filled with beer and jokes and nearly breaking the canoe in half—in this sense it will appeal to a young audience. And that is exactly who Gessner wants to get with his book; he wants to light a fire under those young butts. So it is a manifesto indeed.

Learning the Birds

As Peter sings, I realize I have no idea what the song is referring to. The not knowing adds to the overall sense of the weekend: I know nothing about this song or the history behind it (though it’s not hard to find this information); I know nothing about birds.

We are up before dawn after a sleepless night in perhaps the most bedraggled motel room I have ever stayed in (the bathroom door had been punched in; the shower curtain sagged; the smell of stale smoke and sadness was so thick I could not sleep). The three-mile drive near the Montezuma refuge headquarters sits just south of route 90. So as we look across the foggy fields trying to spot shuffling little birds, the sound of semis roaring east and west joins the faint peeps that rise from the dark soil. We see them, the smallest of shorebirds, the least sandpipers moving across the ground, foraging for food; we see killdeer, a fat little plover, not as cute as his cousin the semipalmated plover.

All weekend Peter is singing, quietly, “From the Halls of Montezuma, to the shores of Tripoli.” We are birding at the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge in northern New York State. The land is flat, grasslands, with pools and mudflats. The Refuge is known as a stopover for shorebirds heading from the Arctic to their warm winters in the south. We were there to see these birds, and to attend a workshop on identifying shorebirds.

As Peter sings, I realize I have no idea what the song is referring to. The not knowing adds to the overall sense of the weekend: I know nothing about this song or the history behind it (though it’s not hard to find this information); I know nothing about birds.

We are up before dawn after a sleepless night in perhaps the most bedraggled motel room I have ever stayed in (the bathroom door had been punched in; the shower curtain sagged; the smell of stale smoke and sadness was so thick I could not sleep). The three-mile drive near the Montezuma refuge headquarters sits just south of route 90. So as we look across the foggy fields trying to spot shuffling little birds, the sound of semis roaring east and west joins the faint peeps that rise from the dark soil. We see them, the smallest of shorebirds, the least sandpipers moving across the ground, foraging for food; we see killdeer, a fat little plover, not as cute as his cousin the semipalmated plover.

American Golden Plover photographed by P. Schoenberger in Kingston, NYWe run into three birders also combing this vast land for birds. They have heard there is an avocet and we all want to see it. So we join forces. Two are young men, 18 and 22, and can see a duck in flight and identify it. That means they know what they are doing. The other is a middle-aged man, a veterinarian from New York City who has embarked on a New York State big year. The avocet will push his list up one more bird.

We drive down a pot-holed dirt road, park and pull out our scopes, peering into the distance. There is the bird, far off, a speck of white with an elegant long bill. It’s thrilling and not. Thrilling because I recognize I’m seeing a rarer species, and not because it’s so far away. I enjoy having a bird fill my binoculars so I can see feathers, and the color of the eye.

We spend long hours, eye to the scope, picking out dots moving across dirt. It’s not satisfying, this museum-like viewing. When an osprey sails overhead, against a perfect blue sky, I am happy. Here’s a big bird I can recognize.

Because I am a teacher, the process of learning is one that interests me. I take a physical approach to learning everything: to be a writer means you have to get up every morning and write. I make this analogy for my students: if you want to run a marathon (ie: write a novel), you don’t just get up and do it. You train, you practice, you stretch, you run every day. That is what it takes to be a writer. I have taken this on with learning about birds. I walk every morning, binoculars at the ready. On the weekends, Peter and I spend long hours in the field, he coaching me, pointing out details of a bird to help me remember. There are lots of nifty mnemonics to help a person remember the songs of birds. Over the past two years of birding, I have developed a vague competence with my local birds. Vague is the correct word. Despite my time and devotion, I am like that diligent student who writes and writes but will always write wooden sentences, or stories without real punch.

Knowing all that you don’t know can have a marvelous effect: a hunger to learn. I felt that hunger when I first began to explore the Hudson River while writing my book. I wanted to read more, explore more; the not knowing was great incentive. Here, realizing all I don’t know has another effect: I’m a tad overwhelmed, the desire to learn replaced by a hollow sinking feeling.

The osprey I do recognize; photo by Peter SchoenbergerThe workshop at the Audubon Center is both entertaining and informative. The teacher, Kevin McGowan, works at Cornell and is an expert on crows, as well as shore birds. He takes us through the basics of shape, size, and behavior. I take notes and think that learning these birds might be possible. He points out the way that the killdeer looks like it is hiccupping, the way that the yellowlegs strolls and picks; the dowitcher is like a sewing machine with its bill in the sand, its head always down.

The next morning we head into the field as a group. We spill onto a dirt road and look long into the distance. Two sandpipers are side by side. Kevin coaxes the details out of us as we peer through our scopes. Does the tail bob up when the bird forages? What color is the chest? What sort of patterning? Slowly we tease it out so that we know we have a Baird’s sandpiper on the right, and a Pectoral sandpiper on the left. I walk away, not entirely satisfied; there is no ah ha moment here.

And I wonder: does it matter that I know this? Maybe a few more years into my birding life it will. But for now what I want is to have an expanse of green in front of me, a blue sky overhead, and the beauty of a bird fill my binoculars. That bird doesn’t have to have a name.

My Reach in the World

As My Reach sails into the world friends have been sending photos of them reading--or not reading. Here are a few. Send me more photos!

Lisa Sanditz on the Jersey Shore

David Ainely, Penguin expert, reading in Antarctica!

Tim Davis, enthralled!

Lisa Sanditz, Colorado

Post-Irene Paddle

I stepped into my boat, noting the cold at my ankles was not the fall-warmed water of a few days earlier. I struck south, passing a wooden dock, sloshed up on shore. Swallows zipped across the water and landed on the wires next to the train tracks. A great blue heron took flight. In many ways, it was just another day for the birds, and for the baby map turtle I saw taking in the last of the day’s sun. But for me, the river was transformed. I recognized everything: the Catskill mountains in the distance, the puff of trees in front of me that is Magdalen Island, the houses on shore that peer down at the river. But the texture of the river was foreign. There was a sense of dereliction, I want to say of lawlessness. It was as if the river itself was not following its own laws, but also that those who live in and on the river had given over to new ways of being, one where anything could and did float off in the river.

I stepped into my boat, noting the cold at my ankles was not the fall-warmed water of a few days earlier. I struck south, passing a wooden dock, sloshed up on shore. Swallows zipped across the water and landed on the wires next to the train tracks. A great blue heron took flight. In many ways, it was just another day for the birds, and for the baby map turtle I saw taking in the last of the day’s sun. But for me, the river was transformed. I recognized everything: the Catskill mountains in the distance, the puff of trees in front of me that is Magdalen Island, the houses on shore that peer down at the river. But the texture of the river was foreign. There was a sense of dereliction, I want to say of lawlessness. It was as if the river itself was not following its own laws, but also that those who live in and on the river had given over to new ways of being, one where anything could and did float off in the river.

The raft of logs and sticks laced with debris was so thick at the entrance to the north Tivoli Bay that I could hardly shove my way through. The water poured out of the narrow entrance to the Bay, pushing me quickly south. There, just a hundred yards off of Magdalen Island was a small island of river junk. A long wooden dock. A large refrigerator and a small refrigerator both knocked against the wood. A pile of sneakers stacked on top of one end of the dock. On the far end, a submerged motorboat, engine still attached was lashed to dock. It too had been dragged south.

So I headed south, seeing a brilliant orange red scarlet tanager in the late day sun, several king birds, and a kingfisher. I thought I might scoot into the North Bay from the southern entrance. But the water there, which I know to be sweet, often placid, was so fast, so violent I knew I couldn’t make my way against the current. So I headed north, taking to the river side of Magdalen Island.