Back on the Water

I settled into my kayak, pushing my back into the seat and my knees up into the side of the boat. I tugged the spray skirt into place, and took my first stroke, my hands adjusting to the paddle. As I glided forward, mute swans flew overhead, the whoosh of their enormous wings like someone bowing the air. This was perhaps the only time of year it is possible to paddle into the Vly as in summer the surface is covered by floating mats of vegetation. But in early spring a wide shallow channel marked the middle of the marsh.

I write back on the water and not on the river because this first paddle of the season was on a freshwater marsh, named the The Great Vly in Ulster County. The weather was warm, the sun out, and the wind blowing—a perfect northeast spring day. The Vly is about a mile long, choked with phragmites, and cattails. Short cliffs and woods rim the Vly on the western side and low hills cradle the eastern side. The tail end of a cement factory is visible at the far northeastern end (Lehigh Cement runs from the Vly to the Hudson River).

I settled into my kayak, pushing my back into the seat and my knees up into the side of the boat. I tugged the spray skirt into place, and took my first stroke, my hands adjusting to the paddle. As I glided forward, mute swans flew overhead, the whoosh of their enormous wings like someone bowing the air. This was perhaps the only time of year it is possible to paddle into the Vly as in summer the surface is covered by floating mats of vegetation. But in early spring a wide shallow channel marked the middle of the marsh.

Peter was ahead of me in his green kayak, his camera cradled between his legs. We passed Canada geese nesting in clumps of grasses, and a few beaver lodge, the sticks piling high like water-based teepees. Ring-necked ducks, mallards and a few teal rose when we got within two hundred yards (ducks are skittish!). At the northern end of the Vly, I followed a narrow path into the grasses. I couldn’t see Peter or the birds. I knew that but a mile or so away in one direction ran the New York State Thruway, and in the other sat the cement plant. But there in the marsh was a sense of still isolation, just a drop of land protected from the rush of the world.

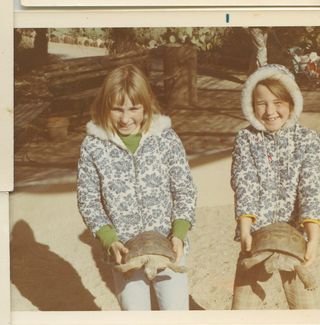

As I paddled about I kept thinking: this smell is familiar. And then it came to me. The Vly smells like my sister’s turtle tanks from when we were children. Inside those tanks was a mixture of algae, turtle poop and then the turtles themselves, a cast of soft shell turtles and painted turtles that lived short but loved lives.

The tanks always needed more cleaning. Every so often, when the water became unhealthily murky, Becky would stick a clear plastic tube into the tank and siphon out most of the water. To get the water flowing, she would fill the tube with water, plug both ends, and if all went well, when she released her thumbs, the water would flow. Often, it did not, so she resorted the most assured way: sucking on the end of the tube. Only she didn’t like sucking on the tube. So she would call in her little sister. “Help me out,” she would coax. And I would. The first time I ended up with a mouthful of turtle tank water. Later, I would watch the cloudy water zooming down the tube toward my mouth and let go just before it arrived. But there I would be, hovering over a plastic bucket of turtle water, inhaling the smell of turtle life.

So there I was, paddling in a large body of turtle water. Which means there had to be turtles.

“I’ve seen five,” Peter said, which didn’t surprise me. Peter sees and hears everything in the woods and streams—the mink by the side of the pond, the grouse drumming in the woods, a thumping beat I would easily miss.

I had seen none. But truth was I hadn’t been looking for turtles, I’d been looking at the eagles soaring overhead, and hoping to see a goshawk as well.

I scanned the shoreline. Peter told me to look on logs, and on the beaver lodges. Turtles like to sun. “Look for something shiny,” Peter said. “And if you are lucky, maybe we’ll see a yellow spotted turtle.” He paused. “They are pretty rare.”

The yellow spotted turtle is on the endangered list in Canada, and though it’s not on that list in this country, it is “vulnerable to extinction in the wild.”

I wanted to see one. What is this urge to see the rare, the species poised to disappear, perhaps in my lifetime? This wasn’t the first time. I’ve made long detours in hopes of seeing a whooping crane, and I’ve tromped through miles of sagebrush to see a greater sage grouse. It is Peter’s stories of when he set afloat in the waters of Arkansas looking for the Lord God Bird—the Ivory billed Woodpecker—that thrill me the most. Somewhere in my thinking is that seeing these creatures means they are still here with us, that things are not as dire as I fear. But beyond this need to be reassured is something else more primitive: seeing them—when I am that fortunate--is special. It’s like being awarded that grant or residency, which always feels like half work, half (or more) chance. Or, it’s like finding that one perfect partner—amongst the several billion on this planet--to venture out with onto a marsh on a spring day.

I suppose my urge to see the rare isn’t unlike someone who flies to Paris to see the Mona Lisa or to Rome to see the Sistine Chapel. But to see these treasures simply requires determination, paying a fee (and usually standing in a long line). And it’s possible to return again and again to see these rarities. To see the turtle would require stealth, a keen eye, and good luck.

We approached the shore where we had put in two hours earlier. My lower back could feel the tender ache of this first paddle. I felt happy, even though I had given up on the goshawk, and had resigned myself to no turtle.

“There,” Peter said, as we neared the shore.

And there they were, two spotted turtles, sunning on a log. We watched them for ten minutes before they slid off the log into the turtle water.

Snake Bight Trail

Snake Bight Trail

Just that morning we had packed up our tent in the Pine Key Campground in Everglades National Park where through the night we listened to the chuck will’s widow sing its eponymous song. We had spent the past three days in the park, walking trails and spotting an amazing range of birds: mangrove cuckoo, anhinga, shiny cowbird, purple gallinule, and limpkin. Overhead, against a light blue sky we spied snail kite, short tailed hawk, swallow-tailed kite, and many osprey carrying food to their nests. Despite this bounty of birds, we still wanted to see one pink creature: the greater flamingo. To see one, we had to walk the 1.7 miles out the Snake Bight trail.

It’s Friday morning and Peter and I are walking around the parking lot of a Burger King in Homestead, Florida. It’s already 80 degrees, and the heat clings to my skin, while grease works it way up my nostrils. This might be the rudest reentry to civilization I have ever experienced in my camping/outdoor life. Reentry is always hard—the sounds and smells too much, the whir of traffic too insistent. But we’re looking for a myna bird, a big billed black bird that obligingly lurks near the dumpster. So fast we are back in our air-conditioned rental car.

Just that morning we had packed up our tent in the Pine Key Campground in Everglades National Park where through the night we listened to the chuck will’s widow sing its eponymous song. We had spent the past three days in the park, walking trails and spotting an amazing range of birds: mangrove cuckoo, anhinga, shiny cowbird, purple gallinule, and limpkin. Overhead, against a light blue sky we spied snail kite, short tailed hawk, swallow-tailed kite, and many osprey carrying food to their nests. Despite this bounty of birds, we still wanted to see one pink creature: the greater flamingo. To see one, we had to walk the 1.7 miles out the Snake Bight trail.

Snake Bight is a flat path (as all the paths are in the Everglades) that leads from the road to a bight, or a bay within a bay (hence the name—you do not get bitten by snakes on the path, though if you are lucky you get to see a snake). Walking this path is a birder’s pilgrimage: every birder who wants to add the flamingo to his or her ABA-area life list has stepped here. I wondered at the hundreds of determined, expectant feet that had stepped here before us (if you have walked Snake Bight and have a story you would like to share, please email me! susan@susanfoxrogers.com).

Most of the path is shaded by mangrove trees, though at noon nothing keeps the sun from blaring down through the small, shiny green leaves. The trail is rimmed by a riot of brush, an occasional red cardinal flower, an occasional prickly pear cactus. Fifteen feet into the brush a murky narrow waterway parallels the trail: perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. And yet the path had a spirit-buoying sweet smell from decaying leaves. Though it was spring in Florida, it smelled like fall in the Northeast, my favorite season.

At the end of the path a boardwalk stretches into the bay where we looked out onto low tide and in the distance hundreds, perhaps thousands, of wading birds. Was there a flamingo among them? No doubt. But even with a scope we would not know. So we walked back, slapping mosquitoes and regretting we had not brought food or water.

When we arrived at our car, we heard branches breaking and a crash as something emerged from the brush. An alligator, eight feet long, long-legged its way onto the strip of short grass near our car and but a dozen feet in front of us. It made a low, guttural hiss. We stepped back. It settled, melting like pudding into the grass, and assumed its napping position.

We were determined to visit Snake Bight at high tide, which would bring the birds in closer. At high tide, the water is a foot, at times two feet deep—perfect for long-legged wading birds. So we got up the next morning, made a brief loop of the Eco Pond, where we saw roseate spoonbills in all of their pink glory, along with white ibis, wood storks, and stilts. Then we made the walk a second time, now in the relative cool of morning. High tide brought the birds a bit closer, but there were fewer birds. We stood, slightly disappointed, watching birds sail through the sky and calling out, “Pink one, heading right.” Pause. “Roseate.” “Pink one, flying left,” I called. “Does it have black on its wings?” I thought I saw those bold lines. “Which one?” Peter asked. Which one? The sky was an infinite blue, the birds an infinite traffic of dots.

Fifteen minutes passed. We entertained ourselves with an immature ibis near shore and attempted to walk out on the marsh so we could be nearer to where the birds clustered (guidebooks warn that people sink, and “disappear”!).

“You know what this smells like?” Peter observed, “when you boil a deer’s head.”

“No kidding,” I said.

He knew he had to explain more. “To get the antlers, from road kill, that’s what I did.”

As a child, Peter hunted. He has long since put down his gun and picked up binoculars but all of those skills of a hunter translate. He sees and hears birds, but he also sees the mink by the side of the pond, a ripple that is a beaver, the coyote slinking through the woods, and the smell of the fox. And, he knows what it smells like to boil a deer’s head.

We were just at the point of giving up on the flamingo when we heard a grinding cackle that is unmistakable: rail. And there was the skinny, secretive bird, scurrying from one tuft of grass to another. And then it had a cousin on the mainland hollering back, and suddenly we had a rail fest, me giddy and Peter snapping photos so he could later piece together if these were King Rail or Clapper Rail.

And it would be good if this story ended with a flamingo winging its way overhead. But birding, like life, is not always so neat. And birding, like life, is most fun when you go looking for a flamingo and instead meet an alligator or hear the cackle of a King Rail.

Photos of pelican, little blue heron and ibis are taken by Peter Schoenberger.

Christmas Bird Count

Christmas Bird Count

When Peter Schoenberger asks me to join him on his Christmas Bird Count I get that this is a special invitation, perhaps the closest I’ll come to a marriage proposal in this lifetime. I need to be willing to live through the good and bad, the sickness and health of a long day, be up at 3:30 and ready to go at 4:30. When I climb into the car at 4:32, I am aware I am late. But that does not stem my excitement. I am experiencing the thrill of Christmas day when I was a child and woke full of hope. I remind myself that that hope was often deflated late in the morning, as the gifts I wanted were not unwrapped. But, without ruining this narrative I can say that my hopes only soared after unwrapping our first gift of birds.

We arrive at our sector “H” within the Mohonk-Ashokan circle at 5 am. The CBC is conducted by marking off circles fifteen miles in diameter. These circles are then randomly divided into sectors, some larger than others, some more choice than others. Within our circle are the wonderful Mohonk Preserve, and a beautiful section of the Rondout Creek. Peter’s long narrow sector H on the western edge of the circle is one he has covered since 2005 and holds nothing of wonder, in fact was unwanted and uncounted for years. He’s affectionate about the spot because it is his and has been for these five years but otherwise he has no allegiance to this area out route 209 past Stone Ridge in Ulster county, New York. It includes winding, narrow roads that move through farms and at a higher elevation pass through forests of both hardwood and pine trees. Stone houses punctuate the landscape, as well as a few trailers. Most of the houses look shuttered in, dark, and plumes of smoke rise from chimneys. In other words, it is much like many areas of Ulster County. There is nothing special about it, and yet every year, Peter tells me, he finds special birds.

When I first heard about Christmas Bird Count, now its 111th year, I didn’t quite understand what it was all about. Counting birds—how was that possible? And why would you want to count birds in the dead of winter, a time where seeing just a few sparrows, a junco or a cardinal is all you get. Birding is fun in the spring, when the warblers move through the Hudson Valley. But if over 60,000 people in more than 2,000 circles nation-wide devote a day—and have devoted a day since the first CBC in 1900—to counting birds, then there must be something to it. Audubon, who sponsors this event, compiles all of the data, and though in some ways it may seem like rough data, it is still possible to get a good sense of what is happening with bird populations. When I look at the early data from our circle—an area that has been counted for 61 years--I note that they do not have an entry for the bald eagle, a bird that is seen now every year. In the 50s, everyone saw a ruffed grouse, a bird no one sees now. This rise and fall tells us about the health of a specific bird species but also about other environmental issues we should be paying attention to (Audubon has a bibliography of scientific articles that make use of CBC data).

It is dark out as we stand on Kripplebush road at 5 in the morning. It’s 23 degrees. The stars are magnificent, clear and bright. We both spy a fleeting falling star, and I don’t doubt that we wish for the same thing (if Peter is sentimental enough to wish for anything on a star): to hear a screech owl. Peter calls the bird through his iPod on the car stereo. The sharp, crazy sound of the screech owl emerges from the inside of his warm car. We stand and wait, listening into the quiet. I hear a rooster in the distance and we laugh together when I admit that for a moment I thought it was a special bird. One car passes us in the dark without stopping, and then the next car on that lonely headlight lit road does stop. “We’re looking for birds,” Peter says, and without hesitation the driver moves on. Perhaps it is ordinary to run into birders at five in the morning but being that birder I know that it is a special moment. It’s not just the cold air snapping me awake it’s the sense of a mission, of a collective hunt. We have a task and we want to do it well. That is, we want to count accurately but also account for as many species as might be making this patch of land their home.

And then there it is, that funny, whinny sound that the screech owl makes coming from one side of the road, then from the other. We both light up, delighted by hearing this voice from the dark. We do not linger to savor the sound of the screech owl, but rather scoot up the hill to a spot Peter imagines would be good for Saw-whet owls. He hasn’t heard or seen any there, but it’s an area dense in hemlocks, near a swamp. The chances of finding this marvelous boreal winter visitor feel slim. But Peter has developed a new faith in the Saw-whet. “People don’t see Saw-whets, because they don’t look for them,” he explains. “You have to believe in them,” he says, as if he is asking me to believe in God.

When we get out of the car we realize that the iPod has frozen, not to return all day. So, improbably, Peter begins to whistle, the hoot-hoot-hoot that rises through the scale. We stand, inhaling the frozen air (now 15 degrees) and looking up at the stars. There we see the longest shooting star either of us has ever seen. It makes a complete arc of the sky, and keeps going, as if plummeting into the trees. Not three minutes later we hear the funny little click that a Saw-whet makes. We both jump with excitement, and then the owl begins to hoot back to us. And another joins us from the other side of the swamp. We have a Saw-whet orchestra going and we laugh with glee. I figure if we only see juncos and Canada geese the rest of the day I will still be satisfied.

We spend some time with the buntings, then move on, driving the roads as they curve and weave. We pick up the expected species, and are unable to count the number of pigeons winging in and out of a large red barn, or the number of Canada geese tromping through a wide field. We stop on route 209, and scan a wide field. In the far distance, I point out a white dot. We pull out the scope. Peter curses. “It’s a good bird and I can’t tell what it is.” He marches off across the field, camera in hand. Twenty minutes later he is back with a report, and a smile: Cooper’s hawk.

Near nine in the morning we stop at a convenience store. I’ve brought two-day’s worth of food: turkey soup (perhaps that is why we did not see a single turkey all day!), ham and cheese sandwiches, chips and vegetables to munch on, cookies, and a thermos of tea. But we need some chocolate to get us through the morning. The stop is a good one. Perched in a tree near the eastern end of the lot is a Merlin. Peter takes photographs of the upright, elegant bird, its mottled chest, long tail, and piercing eyes.

In the mornings while I am reading the New York Times and drinking my coffee, Peter is drinking tea and pondering bird information: lists, books, images. Often I wonder what he is doing, what he sees as he compares notes from one year to the next, as he scans lists. Now I understand that he has been working for weeks, perhaps months, to make this day seamless, to find the species we should find (plus some), to be at the right place at the right time of day. I don’t say anything, of course, but silently I am grateful, and also impressed that we found that red-breasted nuthatch.

The rest of the day unfolds in a daze of counting, walking, stopping, driving. By 4 in the afternoon we have driven 66.2 miles, and walked a few as well. We are exhausted. We plunk down in a field, snacks at hand, scope at the ready, and wait to see horned lark. “The larks will come,” he says in his best French accent. Every year, Peter has seen horned larks at this spot at dusk.

The sun cascades to the west, a gorgeous sunset, oranges in a sharp blue sky, and we wait. Then we worry we will be late for the after-count dinner, an incredible spread created by Mark DeDea and Kyla Haber. We pack up, happy with the 42 species of bird that we saw, and the 1,480 individuals that we counted.

Back in Kingston, the circle unites to offer up numbers and species. Everyone is tired but a bit high from the day, the long hours, the focus. The dark room where we gather is festive, plates set, and the smell of good food permeating the air. Everyone is pleased with his or her sightings, eager to share. We gather at the long table, one big family of birders. I feel like we should say a prayer of thanks to the birds, but instead we eat. Then comes the list.

Leading us is Steve Chorvas, who is not just a birder, but an all-around remarkable naturalist. He’s serious and thorough as he goes through each species. I wait as he calls out Saw-whet. Each sector calls out none. “A pair,” Peter says as calmly as he can, as if this might be normal. I am ready to tell the story of Peter whistling into the dark, but I keep it until later. “That might be considered a rarity,” Steve says, and continues with the list. There are a few other rarities reported for this region: a killdeer, a broad-wing hawk, a ruby-crowned kinglet, wood ducks, and ring-necked ducks. As Steve goes through the list, we learn from our count that Carolina wren populations are up and robin populations are low. Canada geese are doing just fine, but no one saw a pipit.

Steve calls out bird after bird. When Peter reports no great horned owls he turns. “How come you didn’t find any great horned?” he asks.

Peter shrugs, “I guess I’m not very good at this.”

Steve hesitates for a moment. He turns back to his computer screen, ready to move on, but a smile appears and then, still focused on the screen, the smile spreads, his face lights up, and he starts to laugh. Soon, we are all laughing, from the wonderful absurdity of Peter’s comment, from the pleasure of birding all day, of finding a Saw-whet and not finding a great horned, of sharing this deep, odd love of birds.

CBC NYML: 30 people in 10 field parties saw 11,840 individuals of 72 species.

All photos, except the Saw-whet owl, taken on CBC day December 18, 2010 by Peter Scoenberger.

Christmas Bird Count

When Peter Schoenberger asks me to join him on his Christmas Bird Count I get that this is a special invitation, perhaps the closest I’ll come to a marriage proposal in this lifetime. I need to be willing to live through the good and bad, the sickness and health of a long day, be up at 3:30 and ready to go at 4:30. When I climb into the car at 4:32, I am aware I am late. But that does not stem my excitement. I am experiencing the thrill of Christmas day when I was a child and woke full of hope. I remind myself that that hope was often deflated late in the morning, as the gifts I wanted were not unwrapped. But, without ruining this narrative I can say that my hopes only soared after unwrapping our first gift of birds.

We arrive at our sector “H” within the Mohonk-Ashokan circle at 5 am. The CBC is conducted by marking off circles fifteen miles in diameter. These circles are then randomly divided into sectors, some larger than others, some more choice than others. Within our circle are the wonderful Mohonk Preserve, and a beautiful section of the Rondout Creek. Peter’s long narrow sector H on the western edge of the circle is one he has covered since 2005 and holds nothing of wonder, in fact was unwanted and uncounted for years. He’s affectionate about the spot because it is his and has been for these five years but otherwise he has no allegiance to this area out route 209 past Stone Ridge in Ulster county, New York. It includes winding, narrow roads that move through farms and at a higher elevation pass through forests of both hardwood and pine trees. Stone houses punctuate the landscape, as well as a few trailers. Most of the houses look shuttered in, dark, and plumes of smoke rise from chimneys. In other words, it is much like many areas of Ulster County. There is nothing special about it, and yet every year, Peter tells me, he finds special birds.

When I first heard about Christmas Bird Count, now its 111th year, I didn’t quite understand what it was all about. Counting birds—how was that possible? And why would you want to count birds in the dead of winter, a time where seeing just a few sparrows, a junco or a cardinal is all you get. Birding is fun in the spring, when the warblers move through the Hudson Valley. But if over 60,000 people in more than 2,000 circles nation-wide devote a day—and have devoted a day since the first CBC in 1900—to counting birds, then there must be something to it. Audubon, who sponsors this event, compiles all of the data, and though in some ways it may seem like rough data, it is still possible to get a good sense of what is happening with bird populations. When I look at the early data from our circle—an area that has been counted for 61 years--I note that they do not have an entry for the bald eagle, a bird that is seen now every year. In the 50s, everyone saw a ruffed grouse, a bird no one sees now. This rise and fall tells us about the health of a specific bird species but also about other environmental issues we should be paying attention to (Audubon has a bibliography of scientific articles that make use of CBC data).

It is dark out as we stand on Kripplebush road at 5 in the morning. It’s 23 degrees. The stars are magnificent, clear and bright. We both spy a fleeting falling star, and I don’t doubt that we wish for the same thing (if Peter is sentimental enough to wish for anything on a star): to hear a screech owl. Peter calls the bird through his iPod on the car stereo. The sharp, crazy sound of the screech owl emerges from the inside of his warm car. We stand and wait, listening into the quiet. I hear a rooster in the distance and we laugh together when I admit that for a moment I thought it was a special bird. One car passes us in the dark without stopping, and then the next car on that lonely headlight lit road does stop. “We’re looking for birds,” Peter says, and without hesitation the driver moves on. Perhaps it is ordinary to run into birders at five in the morning but being that birder I know that it is a special moment. It’s not just the cold air snapping me awake it’s the sense of a mission, of a collective hunt. We have a task and we want to do it well. That is, we want to count accurately but also account for as many species as might be making this patch of land their home.

And then there it is, that funny, whinny sound that the screech owl makes coming from one side of the road, then from the other. We both light up, delighted by hearing this voice from the dark. We do not linger to savor the sound of the screech owl, but rather scoot up the hill to a spot Peter imagines would be good for Saw-whet owls. He hasn’t heard or seen any there, but it’s an area dense in hemlocks, near a swamp. The chances of finding this marvelous boreal winter visitor feel slim. But Peter has developed a new faith in the Saw-whet. “People don’t see Saw-whets, because they don’t look for them,” he explains. “You have to believe in them,” he says, as if he is asking me to believe in God.

Two weeks earlier, we had gathered with a half dozen other bird enthusiasts to watch researcher Glenn Proudfoot band Saw-whet owls on the Mohonk Preserve. The night we were there, a dozen owls flew into the mist nets, strung between the bushy pine trees. They tangled in the nets as they flew toward the loud call of a Saw-whet blaring into the night air from speakers. They are curious birds, wondering who this enormous cousin might be. The birds, once extracted from the tangle, were stuffed into empty tomato paste cans, their little feet sticking out the bottom. The birds were tagged, weighed, and measured. All the while, I admired the stocky little bird and relished its tenacity as it clicked its bills in protest over being fondled, prodded, flipped upside down. Saw-whets have enormous eyes, and in the light of the warm cabin, the black irises were large circles rimmed by a vibrant yellow. I stood outside in the cold and watched as they flew free, and I wished them a silent good flight. Because I had seen a dozen that night, had touched those so soft owl feathers, I was ready to believe in the Saw-whet, but I didn’t believe it was possible to drive out on a dark road and find one.

When we get out of the car we realize that the iPod has frozen, not to return all day. So, improbably, Peter begins to whistle, the hoot-hoot-hoot that rises through the scale. We stand, inhaling the frozen air (now 15 degrees) and looking up at the stars. There we see the longest shooting star either of us has ever seen. It makes a complete arc of the sky, and keeps going, as if plummeting into the trees. Not three minutes later we hear the funny little click that a Saw-whet makes. We both jump with excitement, and then the owl begins to hoot back to us. And another joins us from the other side of the swamp. We have a Saw-whet orchestra going and we laugh with glee. I figure if we only see juncos and Canada geese the rest of the day I will still be satisfied.

Our daylight hours begin back in farmland. In the grey light of dawn we hear overhead chatter. We look up at what looks like snowflakes. Snow buntings. We walk the edge of the field where they fly and contemplate walking onto the field. “That is exactly what they ask you not to do,” Peter explains. But it is tempting. We take a few steps down a long, dirt driveway and as if we’d pushed a button, a car drives toward us. I flag the car. “Do you mind if we walk down your driveway?” I ask. “Sure, I’m a birder too,” the man says and drives off.

We spend some time with the buntings, then move on, driving the roads as they curve and weave. We pick up the expected species, and are unable to count the number of pigeons winging in and out of a large red barn, or the number of Canada geese tromping through a wide field. We stop on route 209, and scan a wide field. In the far distance, I point out a white dot. We pull out the scope. Peter curses. “It’s a good bird and I can’t tell what it is.” He marches off across the field, camera in hand. Twenty minutes later he is back with a report, and a smile: Cooper’s hawk.

We drive out narrow roads that dead end in secret wooded openings. We pass farmhouses surrounded by pastures with cows, or at one farm, alpacas. A wagon wheel decorates one lawn. As we pass isolated, warm homes, I wonder as I so often do what people do with their lives here in the woods. Do they work in Kingston, a half hour drive away? Or have they figured out a country life, growing their vegetables and storing potatoes to make it through the winter? We search for bird feeders, and count the expected juncos, house sparrows, titmouse, and somehow all day manage not to see a house finch. Despite our movement, and that the temperature is now into the 20s, I’m cold. I’m wearing four layers of pants, and the same on top. I’ve got heavy, white bunny boots on my feet (an early Christmas gift from Peter). These are the same sorts of boots I was issued by the National Science Foundation and wore in Antarctica. There, I stood around for five hours one day counting Adelie penguins and never felt a twinge of cold. Is it possible the cold of Ulster County is greater than that on Ross Island? I slip hand warmers into my gloves and into my boots.

Near nine in the morning we stop at a convenience store. I’ve brought two-day’s worth of food: turkey soup (perhaps that is why we did not see a single turkey all day!), ham and cheese sandwiches, chips and vegetables to munch on, cookies, and a thermos of tea. But we need some chocolate to get us through the morning. The stop is a good one. Perched in a tree near the eastern end of the lot is a Merlin. Peter takes photographs of the upright, elegant bird, its mottled chest, long tail, and piercing eyes.

Mid-day Peter says, “We need a red-breasted nuthatch.” I am holding the list in my hand; Peter is holding the list in his head. He turns the car and drives out to deep woods, a stand of pine trees where he knows a red-breasted nuthatch should be. We find it. It is so precise, so easy that in that moment I realize that most of the birds we have seen have not been found by luck or by accident (except, perhaps, that Merlin). Peter knows where certain species live in this sector because he is familiar with it, and he knows what lives here in winter. But more than that, he thinks about each bird, what sort of habitat it needs, what time of day it moves to get its food. So often when we are birding he will comment, “We really should be seeing X,” and then, as if he has conjured the bird, X appears. And so in the crooks and bushes, the trees and fields of this patch of Ulster County he is attune to where the birds will be looking for a berry or a mouse and at what time of day they might be busy doing so. And all day, we have been there to see, to count, to admire, to accept yet another gift.

In the mornings while I am reading the New York Times and drinking my coffee, Peter is drinking tea and pondering bird information: lists, books, images. Often I wonder what he is doing, what he sees as he compares notes from one year to the next, as he scans lists. Now I understand that he has been working for weeks, perhaps months, to make this day seamless, to find the species we should find (plus some), to be at the right place at the right time of day. I don’t say anything, of course, but silently I am grateful, and also impressed that we found that red-breasted nuthatch.

The rest of the day unfolds in a daze of counting, walking, stopping, driving. By 4 in the afternoon we have driven 66.2 miles, and walked a few as well. We are exhausted. We plunk down in a field, snacks at hand, scope at the ready, and wait to see horned lark. “The larks will come,” he says in his best French accent. Every year, Peter has seen horned larks at this spot at dusk.

The sun cascades to the west, a gorgeous sunset, oranges in a sharp blue sky, and we wait. Then we worry we will be late for the after-count dinner, an incredible spread created by Mark DeDea and Kyla Haber. We pack up, happy with the 42 species of bird that we saw, and the 1,480 individuals that we counted.

Back in Kingston, the circle unites to offer up numbers and species. Everyone is tired but a bit high from the day, the long hours, the focus. The dark room where we gather is festive, plates set, and the smell of good food permeating the air. Everyone is pleased with his or her sightings, eager to share. We gather at the long table, one big family of birders. I feel like we should say a prayer of thanks to the birds, but instead we eat. Then comes the list.

Leading us is Steve Chorvas, who is not just a birder, but an all-around remarkable naturalist. He’s serious and thorough as he goes through each species. I wait as he calls out Saw-whet. Each sector calls out none. “A pair,” Peter says as calmly as he can, as if this might be normal. I am ready to tell the story of Peter whistling into the dark, but I keep it until later. “That might be considered a rarity,” Steve says, and continues with the list. There are a few other rarities reported for this region: a killdeer, a broad-wing hawk, a ruby-crowned kinglet, wood ducks, and ring-necked ducks. As Steve goes through the list, we learn from our count that Carolina wren populations are up and robin populations are low. Canada geese are doing just fine, but no one saw a pipit.

Steve calls out bird after bird. When Peter reports no great horned owls he turns. “How come you didn’t find any great horned?” he asks.

Peter shrugs, “I guess I’m not very good at this.”

Steve hesitates for a moment. He turns back to his computer screen, ready to move on, but a smile appears and then, still focused on the screen, the smile spreads, his face lights up, and he starts to laugh. Soon, we are all laughing, from the wonderful absurdity of Peter’s comment, from the pleasure of birding all day, of finding a Saw-whet and not finding a great horned, of sharing this deep, odd love of birds.

CBC NYML: 30 people in 10 field parties saw 11,840 individuals of 72 species.

All photos, except the Saw-whet owl, taken on CBC day December 18, 2010 by Peter Scoenberger.

First Bird of the Year

So on this first year of a New Year ritual, I want my first bird to be a good bird. I try and be democratic in my birding, to admire the chickadee as much as the harrier scanning low over the field, but it’s just not possible. The harrier, because seen only once in a while, is a treat, while the chickadee is my daily bread. I need them both. But I do not want the chickadee to be my first bird of 2011.

On December 31, as we go to bed an hour before midnight, Peter tells me that the next morning I need to pay attention to the first bird of the year. We all have our January 1 rituals. I always write, as if that will set the tone for the year. I always go outside to hike, or cross country ski if I am lucky enough to have snow. Since I am new to birding, I think of this as a fresh ritual, marking a new year of seeing, admiring, even loving the birds. For I do love the birds, for themselves—the way this one is a vibrant blue that melts into an orange chest, or the way that one flies in slow loping wing beats, how another makes its living hammering its head against a tree. And in particular I like the ones that secret themselves away during the day only to swoop out at night. But I also love the birds for what they do for me: make me focus in the outdoors. Looking at birds, I shift my gaze from the inside worries or small concerns to pay attention to a wing bar or the shape of a beak. I like the way that my mind settles when I look through my binoculars.

So on this first year of a New Year ritual, I want my first bird to be a good bird. I try and be democratic in my birding, to admire the chickadee as much as the harrier scanning low over the field, but it’s just not possible. The harrier, because seen only once in a while, is a treat, while the chickadee is my daily bread. I need them both. But I do not want the chickadee to be my first bird of 2011.

I have just lived through one of the richest, most fulfilling years of my life, and I am staring into 2011 with a bit of trepidation. Deep in my soul I believe in the balance of things. A good year, a bad year. Looking at birds, I should know that balance is not natural, excess is. Exuberance. Still, I’m a bit superstitious and I know I cannot match my trips (Tasmania, Maine, Wyoming, Paris), my book contract, my falling in love of 2010. Here is where the birds might save me. In 2011, I know I will see more as well as more glorious birds than in 2010. And yet just two days ago I saw a bird that I may never see again in my life. It is not that it is a rare bird, one of those wanderers from Siberia or South America (though I did see one of those—a fork-tailed flycatcher—in 2010). Though it is endangered in some states, and of concern in others, it is a widely distributed bird in the United States. But it is so secretive it is rarely seen.

The chance of hearing an owl in a lifetime is pretty good. Many can imitate the “who cooks for you” of the barred owl, or the hoot of the great horned owl. But to see an owl is more difficult. Last March, at dusk I saw short-eared owls soaring across a wide field that was once a landing strip, and I have seen a barred owl perched in a tree. But to go out into the woods and to look up inside of trees to find an owl—that is like looking, as we say, for a needle in a haystack. But it can be done. I have decided it will take patience, time, and thinking like an owl.

Of all of the owls, one of the hardest to find is the long eared owl. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology site (my Bible for online birding) writes: “Though widespread and relatively common in its range, it is rarely seen.” Peter tells me he has seen a long-eared owl but only when he was pointed to the bird. He even paid five dollars once to look at a long eared owl in California. It is hard to see because it roosts in dense evergreen forests, and it rarely vocalizes.

Despite the odds, Peter tells me we are going to look for a long-eared owl. We are walking on the beautiful, open land of the Pennypack Land Preserve adjacent to his childhood hometown, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. It is mid-morning. It is two days before New Year’s, two days before Peter’s niece is to be married. We are in Pennsylvania for the wedding, not to go owling. But we have walked on snowy trails around a wide field planted beautifully with native grasses, now golden in the winter. A harrier glided by early in our walk. At the edge of the field is a stand of stout, dense spruce trees. Perfect habitat.

Peter focuses his birding on habitat—you can’t just go out and look, you have to look in the right place. That means understanding the birds, what they need to eat, how they live their lives. There is not much we know about these long-eared owls. But we do know they need shelter in the day, and a wide field at night.

We walk into the trees, the early morning light barely filtering through. Steam rises from my breath. As I begin to peer up the trees, through the branches that poke me in the face, the arms, that snap off as I wedge my way in deeper, I meditate on how many hours I have spent doing this. Through the fall I have craned my neck, and wrestled through dense pine branches looking in particular for saw-whet owls. Despite these hours I have never stumbled upon an owl. Yet I still go out, hope overcoming facts.

I wonder if I am wasting this middle-aged life of mine, wandering through trees in the cold. Perhaps. What I do know is that if I don’t go look, I definitely won’t see an owl. And I do want to see an owl, an desire that has no beginning and no end.

As I focus my eyes, shifting field of vision, I worry that if an owl were right there I would not see it. I puzzle whether I am looking for shape or color. Peter tells me about his wonderful trip to Amherst Island in Canada, where there were owls, saw-whets in particular, in the trees. “Just a blob sitting there,” he tells me.

We wander through the trees for a short half hour. Peter is back in the open, soaking in the warmth of the sun. I am not willing to give up on the owls yet. I stop, noticing a patch in the snow, which turns out not to be a pellet. But it is enough to make me look up. And there, staring down at me, are two yellow eyes. The bird takes shape, its slender body and those long, almost goofy looking ears. It is a moment I have been anticipating for so long it feels normal, and also completely unexpected. I look more closely to be sure I have not hallucinated the yellow eyes.

I keep my voice low and steady. “Peter, I have a new year’s gift for you.”

He doesn’t come right away.

“I’m serious, I found you a present.”

He walks toward me. “What is it?” he asks and I do not answer. He has to see for himself. “This better be worth it,” he says, mock grumbling.

I am focused on the bird, not wanting to turn my gaze away. It is as still as can be, hoping I will leave.

“Oh my, Sus,” Peter says, standing at my side in the cold, looking up at what is looking down at us.

The bird has that marvelous facial disc of all owls, but its face looks elongated, egg-shaped, not round. A rich burnt orange frames its face, and the hooked beak is almost completely covered in feathers. White stripes run down the center of its face. Its body is mottled, blending in with the branches that frame it. But what stands out are the ears, as if a child had drawn an owl and mistakenly given it bunny ears. It did not waver, looking down at us from its perch about fifteen feet up, its eyes piercing, challenging us to move on. It held us in its gaze, never blinking, as we spoke the silence of owls.

There is only so long you can look at an owl. They always win at a staring contest. So we returned home to coffee and warmth, and to tell anyone who would listen about our bird. An hour later we headed back out so that Peter could photograph the bird. And

That bird is added to the list of treasures of 2010. And I never expect to be so lucky again, to look up and see yellow eyes staring down at me.

I woke at 6 on January 1, 2011. Peter was still breathing the regular, even beats of sleep. I lay still in the cold room. I could hear his brother snoring from down the hall. The heat turned on, a whoosh of heat rising into the air. And over all of this I heard it, in the distance. Who-who-who-who. I sat up, pulling the blankets off of Peter.

“Did you hear that?” I whisper, waiting to hear it again.

Peter, who hears through his sleep, says, “yes,” then pauses, waiting for the hoot again. “But the rhythm isn’t quite right.”

Is it a dog I am mistaking for an owl? We wait. And then there it is, close enough that it is distinct through the noises of the house. The great horned owl: my first bird of 2011.

I am looking into the New Year with hope. And maybe there will be other owls, snowy or barred, boreal or great grey in the New Year. Maybe.

All photos taken by Peter Schoenberger