Fishing

In 1972, aged 12, I was invited by my cousins for a week of outdoor adventure on their island, Eagle's Nest. It is a drop of an island in Trafalger Bay, which is part of the Northern Lights Lakes in Canada. I spent that week building a tree fort, swimming in the clear cool water, and fishing.

Only on my last day did I catch a fish, an event that startled me as I had given up hope. What surprised me most was how the fish fought. Though it wasn't a large lake trout, it took everything I had in my little arms to reel it in. I remember nothing beyond bringing the fish in, the thrill and satisfaction of that. Certainly the fish was killed, cleaned and eaten. But not by me.

This July I've returned to the island with my cousin Polly and I knew fishing would be a part of our time, in between the swimming (and birding). Since 1972, I've fished but one other time so I have not perfected my cast or my technique on bringing a fish in (that trip in 1972, I lost a lot of lures, irritating the adults who had purchased those lures). Before we left on this trip, Polly left a phone message: you have to club the fish dead. I left a message in return: no way.

The island holds a sort of mythological place in my life. That week in 1972 played a big part in my early love for the outdoors. There on the island I experienced a life lived close to the rhythms of the birch and hemlock, the trout and loons. It was a life I knew I wanted. I was curious how these early, perhaps glorified, memories would measure up to what is there. And I worried that perhaps age and the mess of life would intrude on the simple beauty of being there.

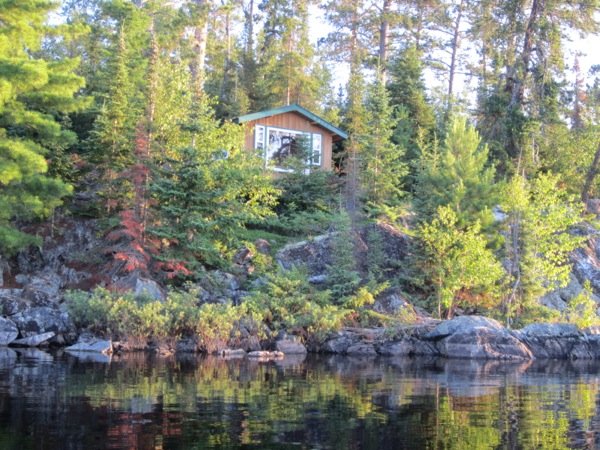

Except for a new large cabin built by my cousin Andrew, the island is remarkably the same as I remembered it. The light in the main cabin remains muted, perfect for games of backgammon or scrabble. Despite some (wonderful) improvements like a propane run refrigerator, the texture of life felt the same. There is no outside world, no internet or phone. The quiet is profound beyond all of my memories. In the late evening and through the night, the stillness was punctuated by the call of loons. Morning and evening the resident baby Merlins begged for food.

Our first full day, Polly woke me in my nest in the summer cabin, perched on a southeastern bluff, with coffee and fresh blueberry muffins. We then spent the morning swimming--naked--around the island. We pulled out on Blueberry Island and ate a few freshly ripe berries and warmed up. My hands were tingling from the cold. Our swim took hours, bobbing in the cold water, back stroke, breast stroke, a bit of a crawl. The day unfolded, endless and endlessly beautiful, except for the mosquitos. They buzzed our ears, bit our ankles and hands. These Canadian mosquitos made those I had encountered in Alaska in June seem fat, dumb and slow. These mosquitos had speed and agility on their side. I could smack one and it would rebound--flying off to bite again.

By late afternoon we were ready to venture out onto the water again, this time in a canoe. To fish. "You need to provide us with dinner, cousin," I said in mock seriousness. Polly had shopped for food for five for this week--we hardly needed any food. But I loved the idea of eating our own fish. I didn't bring up how it was going to get from the water to our plates.

We explored neighboring islands while Polly cast, and reeled in the line. The act alone felt right and good, the time meandering a pleasure.

So it surprised us both when Polly snagged the fish. It hardly struggled, but rather landed peacefully in the net I held. "Smallmouth bass," she said. It lay on the bottom of the tin canoe, without flopping or flipping. Later, we read about smallmouth bass: When hooked near the surface a smallmouth will ordinarily jump high into the air and can often shake the hook or lure from its mouth. When hooked in deep water the fish is a determined, powerful fighter, and even after it has been landed it flares its fins, clamps its jaw, and continues to look and act belligerent. The smallmouth bass is a fish that just won't quit." Really? So our fish's resigned calm became a mystery. But more: isn't fishing the most metaphorical of activities? In 1972 that fish had taught me about persistence, had given me insights into my little life, had maybe even contributed to the writer I have become. Forty years later, I wanted the same insight-inspiring sort of fight. Instead, this weak foot-long smallmouth bass had deprived me of some dazzling metaphorical insight about human nature, life and death. I was feeling mildly cheated as we made our way back to shore.

I quickly struck a deal: you kill the fish. I'll cook it. I saw that I had left Polly with the dirty work. She agreed, but she needed to be reminded of how to clean the fish. I fetched the Joy of Cooking, which contains information on killing and cleaning everything from snapping turtles to snipe and woodcock (I learn the entrails of woodcock are good flambed briefly in brandy).

Polly had no trouble scaling the fish. Then I read, as if from the Bible itself: "Next, draw the fish. Cut the entire length of the belly from the vent to the head and remove the entrails. They are all contained in a pouchlike integument which is easily freed from the flesh, so evisceration need not be a messy job." I contemplated the words integument and evisceration looking out on the water, while Polly executed her task. I read on, channeling Erma Rambauer, taking Polly through the steps of cleaning the fish. Polly's cleaning was a neat job. Erma would have been proud, and so was I.

Our fishing had not led me to thoughts on tenacity, strength, life and death. But as I stood there, looking at the lake, I saw that the real story is about cleaning the fish, facing the pouchlike integument. So much of life is about facing the pouchlike integument.

Our fish was tender and delicately flavored cooked in butter with lemon on the side. I thanked my cousin who had remembered to buy lemons, who had cleaned that fish without complaint. As we ate our simple meal, I felt that forty years had passed and yet no years had passed. We watched an orange sunset as calm settled over our isolated island.

Cousin Polly fishing; my cabin and writing retreat; sunset

Nome

Usually when I travel I contemplate: could I live here. Most of the time I conclude yes, and often fantasize the different life I would have if I moved to Wyoming, returned to Tucson, set out for northern Maine. But on this trip I have not imagined living in these isolated Alaskan towns. I feel the shadow of winter even amidst the spring abundance and the long days of sunshine.

The other day I stepped into a tiny gift shop in Nome. A young blond woman greeted us, and like most conversations in Alaska began with where we are from, why we are here. I quickly turn the questions around, more curious about why someone lives in Nome. She moved here from Utah with her husband, who is originally from Anchorage. They thought they would come for just a few years, but have had two children and plan on staying. "I love it here," she said, as radiant as the sun itself. She loves the pace of life, so much slower than Utah. She loves how neighborly people are, helping out in any situation.

I have not gotten a feel for this town at all as we drop into our hotel late--around 9 at night, under a high sun--eat, and fall asleep only to head out early the next morning in search of more birds. The hotel we are staying in could be a hotel anywhere in the world. Perhaps the only difference is that an animal channel runs continuously in the lobby on a large TV, not the news or a basketball game. And those who clean the rooms in the morning are all men, from a range of places (many Asian, some Native). One tells me he moved here two years ago for work after years of unemployment in Los Angeles.

Our group has stuck to eating at three locations: a place with a very un-appetizing name, Airport Pizza, that actually has fairly good food; Milanos, which serves both pizza and sushi (I can't bring myself to order sushi at a place called Milanos), where the server is Korean; and Subway. Until a week ago I had never eaten at a Subway; now I can say that I've eaten lunch from there every day for a week. Some days I've had breakfast there as well. And though it may seem like I'm complaining, I'm actually grateful that we are not eating at the place that advertises BBQ Chinese.

It is strange to be such a distant tourist; usually I get my hands dirty exploring back alleyways and talking to locals in cafes (or in this case, bars). But we've stayed together as a group, pointing our lens out to the birds we've come to see.

Still, as I've walked through town I've noted the bust of Amundsen. I know Amundsen from his South Pole feats (that is, first to the Pole), but now know that he flew over the North Pole in 1925. I have noted the plaque that celebrates that Wyatt Earp came, established a saloon, and left town with $80,000 in 1901. And, of course, Nome is the end of the Iditarod, the annual dog-sled race that commemorates that moment in 1925 when sled dogs brought serum from Anchorage for the diphtheria that was killing off the city. Imagining the winter here I have even more respect for those mushers.

Nome is a gold town. In 1899 three Swedes discovered gold and a year later the population hit 12, 500. There were bars and saloons and a good Red Light District. In this sense, Nome is a Western town with wide, empty streets and a love of its rough past. The air after rain smells like the desert, not mesquite, but the smell that comes when rain hits dust.

In Nome, people are still searching for gold off shore. Within sight of town are several dredges working the bottom of the Bering Sea. When I walked out the beach the other day, black sand under my boots, the cold of the water licking my cheeks, I saw a young man launching his inflated boat to return to his dredge. "Do you need help?" I asked. He shook his head no, timed his launch to the wavelets and pushed off, only getting his boots a little wet. As he rowed his dinghy toward the dredge, the Bering Sea looked vast and cold. Finding gold has never been easy business. Our group leader ran into a man at the gas pump filling five containers with gas to run his dredge. "I do this every day," he said. With gas at $5.95 a gallon, finding gold isn't cheap either. But we're all looking for gold in one way or another and as we know, the hunt is never cheap.

I walked a bit further and a young man caught up with me, wearing but a long-sleeved shirt while I had on three layers of clothing. He had two corgis bounding about with him, both black and white. They trotted up to me, joyous in the wind. "How do those dogs do in the winter?" I asked. Clearly I am obsessed with how someone gets through a winter out here--including the dogs. He hesitated a moment. "They look like porpoises bounding through the waves, only its snow," he said. And with that image, I turned around and headed back to the hotel.

Photos above: Main Street Nome; The end of the Iditarod; Young man heading toward his gold dredge in the Bering Sea

Bristle-thighed Curlew

I had the honor of being the faculty speaker at this year's Baccalaureate at Bard College. I began my short talk to this year's graduating class describing a special bird, the Bristle-thighed Curlew. It's a medium sized shore bird that makes an amazing migration every fall from the Yukon to Layson in the Hawaiian Islands without eating or sleeping. That's 2,500 miles. Such determination, such commitment to one's own life is what I was urging onto the young men and women walking into the world with their new degrees. Make your choices and go.

But I also had the idea that if I brought the Curlew into my speech I would be bringing the bird closer to me and perhaps, perhaps, this would bring good luck: I would see the Bristle-thighed Curlew while in Nome.

Our group gathered at 5:50 to head out the Kougarok Road and would return to our hotel only 15 hours later. There are three roads out of town: the Teller road leads to Teller; the Council Road to Council. This road leads approximately 80 dirt miles to nowhere. What it follows is the Nome river, which has carved a wide, broad valley between mountains. The views were spectacular over the tundra. We stopped at many places along the way, finding Arctic Warbler and many Gray-cheeked Thrush. Willow Ptarmagin, the state bird, dotted the edges of the road--we counted 18 as we sped along. Dust swirled into the van, as we all scanned, finding birds--the Long-tailed Jaegers in flight, or the Harrier working the field, or the Golden Eagle, soaring high across the tundra looking for voles. We also stopped for Musk Ox, Red Fox, Moose, grazing the hillsides. On the return, a blond grizzly rambled through the bushes, poking its head out as we strained to catch a look.

This road, this area, is our guide Kevin's domain and he knew just where to stop to find that nesting Gyrfalcon. Through scopes we could see the powerful bird high up on the cliff, sitting on its nest. He knew that the road into a camp area was where we would see Bluethroat, a magnificent little bird with a vibrant blue throat. It flew high into the air and then sailed down into the low bushes, as if parachuting from on high.

It was all like being on a magical animal tour, all of the animals just where they should be. I doubted that finding the Curlew would be as easy. In the materials for this trip they mention the Curlew hike--up to two miles, through hummocky terrain. Both Peter and I started small but focused exercise regimens to get into shape.

We parked at the top of a pass, sloping mountains rising to either side. Our group poured out of the van and I was impressed that all but one--who had been sick all morning--headed to the hills. This included the out of shape and the over-70. I only hope I have such gusto at that age.

The field extended out wide before us as we charged uphill. We spread out, hoping to flush the bird, and from time to time stopped to scan, searching for a head poking through the grasses and low bushes. The walking was a bit treacherous, the hummocks seemingly flat but in fact wobbly, unstable footing. The uneven terrain was perfect for twisting an ankle; there were stories from a previous trip where a woman broke her ankle and the rescue took nearly all night.

Another group of birders arrived, giving us even more mass in the wide field. We saw a raven harassing some birds and that led us all toward the western slopes. Sure enough, within minutes we had our binoculars and scopes on the droopy-billed shorebird. With so many of us in the field, we stayed far back, only getting distant looks. The hunt was not nearly as rigorous as I had imagined and perhaps seeing the bird not as magical as I had hoped. It was a bird that so existed in my imagination--magical because of its name, because that migration had me enthralled, because the lesson I offered to those graduating students was one I wanted to take for my own life--that it was almost sure to disappoint. Walking that wide open field I did not come to any resolutions (except: drink more water; get more sleep). But I felt that quiet elation I feel in empty land, the emptiness giving me hope.

photos: Willow Ptarmigan; Musk Ox; Bristle-thighed Curlew field; grizzley!-photo by Peter Schoenberger; Bluethroat--photo by Peter Schoenberger

Carvings

Every evening when we settle into dinner the local men and women show up. They take a seat at the long table where we eat our meals and pull carvings out of their pockets and place them gently on the table. Some are carved of ivory, small and delicate. Some in fossilized sea lion or walrus bones. There's a wonderful range and each time I looked and I rarely bought anything, until a man showed up with a fossilized walrus penis--an Oosik, in Native language--which is two feet long; I simply had to have it.

It's an odd moment, these sales. To see the work of the local people is a treat, but you can't buy everything. So many sit, and sell nothing. One man showed up at dinner every single night with the same ivory bird carving no one wanted. I felt badly for him and the bird.

This land and its people were a puzzle and fascination to me for the length of my stay. Gambell is a subsistence village in that they live off of what they hunt--whale (they are allowed eight strikes a year), birds, fish, walrus, polar bear. While we were in town two polar bear were killed. But all of this is done on ATVs, or boats with outboard engines, with guns, while they are wearing North Face down jackets and a pair of Levis. Any poetic image I had of people in skin kayaks with harpoons is utterly false.

While one carver negotiated a price on his work his cell phone rang. The disjunction between the work of art, which has a long history, and the phone in his hand left me confused. My guess is that these locals in Gambell are also confused, but I wasn't there long enough to ask questions that could give me some insights. But I sure wanted to know:

Who was the first one of these natives to get a four wheeler? who was the first person to bring in a satellite dish and a television set and what on earth do they really think of dancing with the stars?

One carver told me he was 25, had never left Gambell. "But my brother did, he moved to Michigan, married a woman there." I thought about that for a moment.

"How did he meet a woman from Michigan?"

"On the internet." I suppose I could have figured this out but still, I was astonished. His brother wants to return to Gambell. I asked what his wife thought of that.

"She thinks it's too cold here."

I laughed.

He told me about the hunt we had seen that afternoon--hunting for walrus, not whale. "We have enough meat in every freezer until next spring," he explained.

Another man (not a carver) I met told us he left Gambell once, visiting Los Angeles. His cousin had leukemia and the Make a Wish Foundation granted his cousin's wish: that they go to a Lakers game. They did. "The Lakers won," he said with a big smile. We were standing close enough that I could smell alcohol, even though the village is officially dry.

Birders have been coming to Gambell since the 70s (I wish I knew who the first birder was to realize this was a "hotspot"). But the one lodge is all there is for visitors and the range of permits needed to walk and bird the area are daunting (one reason we opted for this tour). There is no place to eat in town and visitors bring all of their food (coolers were regular pieces of luggage on the plane). And you have to walk everywhere, unless you opt for paying someone to take you about on an ATV or manage to "rent" one from someone. The Natives are not making this into a tourist destination--there's not a t-shirt or postcard to be bought--which is one of the reasons it felt so special being there.

Despite the fact white people are nominally present--the birding season is perhaps a month long in spring and the same in fall--the impact of our world is enormous. It begins with oil and guns. It extends to TVs, the internet and cell phones. The local people are worried they are losing their language--Siberian Yupik--as all now speak English. It is a community so small, so vibrant, you can almost feel it wrestling with its own soul. "It's the subsistence hunting that makes this village alive," one man told me. I'm hoping that spirit of the subsistence hunt can weather the onslaught of the outside world. And what I will hold onto are those carvings, and the silent men and women pulling pieces of ivory from their pockets for us to admire.

photos above: carving on fossilized walrus cheek bone; an oosik.