Michael Werner

A few days ago, I called my rock climbing friend Rich Perch,

who lives in Colorado

“What are you doing inside on a glorious day?” I said

without a hello. I was full of the early autumn glory of the east coast.

“It’s hailing here. And lightening.”

He’d been climbing in

the morning but had retreated to his home in Estes Park in the afternoon.

I’ve known Rich since I started climbing in 1975. He and

Thom Scheuer were thenthe rangers

at the Gunks, a world-class climbing area in New York’s Hudson Valley. I

remember walking down the carriage road beneath the blocky, sheer cliffs, and

seeing the two of them in the back of their blue Toyota pick up trucks reading

the New York Times, collecting day fees and bantering with climbers. The moment

I saw them I knew this was a world I wanted to be a part of.

Since that first encounter, Rich and I had shared a rope for

days at a time, as well as many friends, some of whom, like Thom, had died.

“Tomorrow is my anniversary,” Rich boasted.

“You’ve never been married,” I pointed out.

“Tomorrow is the day of my first climb, forty years ago.” Rich

has a list of every climb he has done and with whom.

I tried to think back to the date of my first climb, now 39

years ago. I can picture the thick, stretchy goldline rope and the cliff

itself, a crumbling piece of rock in Huntington, Pennsylvania. I can even smell

the hesitant fear I had then at 15, when I was told to fall, to learn to trust

the rope. I can remember the

mixture of pleasure and thinking this was crazy all bundled together. I don’t

remember the date of that first day at the cliffs, but I know that that fall

day draws the line in my life. Before, I was a teenager with energy but no

focus, after that day I had a passion that has kept me looking skyward, and led

me to climbing areas around the country and overseas.

It’s not

surprising, then, that my first lover was a rock climber. I confess that I

remember a lot less about that first time and that the shift before and after

was hardly the monumental one I had so imagined.

I congratulated Rich on 40 years of happy marriage to the

cliffs of New York and Colorado, California, Nevada, Arizona.

Rich is a funny man, prone to puns, which I actually laugh

at. But for a moment his voice became serious. “Listen, I have to tell you

something. I learned that Michael Werner killed himself last fall.”

I waded through twenty-eight years to remember the blond

skinny man I fell in love with. For a moment I didn’t know what to say—his

suicide didn’t entirely surprise me but his death did.

Before I met Michael I was half in love with him. I’d grown

into climbing on Werner brother stories that made both Michael and his older

brother Peter heroic. The grandest feat was Michael’s 150-foot fall at the

Gunks. He hit the ground, breaking both legs. But he was still alive. A few

weeks later he sawed off his casts and was out climbing. When I met him, I

found the way that his long skinny legs bowed particularly sexy.

I met Michael in Colorado the summer I graduated from high

school. My climbing partner, Neil, and I climbed during the day and usually

camped out in the Eldorado parking lot, but from time to time we showed up hoping

to scrounge a meal or a shower at the house Michael shared with some mutual

friends.

Michael was not immediately taken with me. In fact, I wasn’t

entirely sure he even liked me. He was older (a worldly 24 to my 18) worked in

a tool die factory, smoked, listened to Dire Straits and drank a lot of beer

then spouted his political views, which were so far right I thought he must be

joking. Or drunk. We didn’t really have much in common except for the climbing.

Still, after watching him move on the rock—he had delicate precise footwork—I

was smitten.

I spent my freshman year of college hoping to hear the phone

in the hallway ring and then that one of my dorm-mates would tell me it was for

me. I fantasized Michael arriving in his wide Buick Wildcat to say we were off

to climb in the Black Canyon or nearby in the Garden of the Gods. But he didn’t

call until February—I’d given up hope and had found a boyfriend—to ask not for

a date but did I want to go to Tuolomne for the summer. I said yes.

He came down the next weekend and we climbed together. But I

didn’t see much of him after that until he called in April to say his car had

died, did I mind hitchhiking.

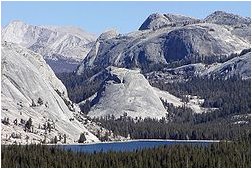

So early June after my sophomore year, Michael and I stuck

out our thumbs and headed to Tuolumne Meadows, which rests at 9,000 feet in

Yosemite National Park.

Every morning that summer we hitchhiked to the rounded granite

domes that make up the glory of Tuolomne climbing. Hitchhiking was easy because

everyone picked us up—mothers alone with their children, tourists from France,

other climbers fortunate enough to have a car—because we looked so wholesome

and we were (if a bit unwashed). For hours every day we tip toed our way up

smooth solid gray rock, testing our finger strength but more our minds that

bent with staring at scarce protection and long falls. Michael appeared

fearless, taking the sharp end of the rope on fantastic leads. I cheered him on

through moves where he hesitated—he was, after all, immortal. His constant play

with the edge was not suicidal, it was a celebration of life. He wanted the

next hold; he reached for the summit.

Most days we arrived back at our tent with just enough

energy to cook a meal and crawl into our sleeping bags. Back in Boulder,

Michael often drank too much, but there in the mountains we didn’t want (and

couldn’t afford) beer. I don’t think I have ever been so physically satisfied

or openly happy. By the end of the summer we were both scrawny and strong, and

climbing hard. And in love. With climbing.

We both kept journals, writing every morning over coffee,

and for Michael a cigarette or three, at our camp table. At the end of the

summer we agreed to swap, an idea no therapist would think good for any

relationship. Mine was filled with meditations on my love for Michael played

out through the rope that kept us bound on the rock. I wrote with all of the

obvious, juicy metaphors between climbing and love—the commitment it took, the

patience, the ability to anticipate when Michael would move up or fall and my

ability to catch him if he did. I literally held his life in my hands and I

found this glorious. But really, my journal was mostly filled with an

overwhelming self-satisfaction, a dreadful ego that perhaps a young climber

needs but that I would rather never claim. To read that journal now is pure

embarrassment.

I peeled apart Michael’s notebook and read his neat

handwriting. Climbs listed by name and grade, his fear, some drama, some humor.

He was a good writer, a good story teller, spare and crisp. My name didn’t

appear once.

That fall, I came undone in college. My studies (Nietzsche’s

overman!) and the climbing collided so that when I went home at Christmas I

didn’t want to go back. It was easy to blame some of my problems on Michael and

so I did and so the relationship ended. The love of my life lasted for a year.

Michael killed himself. What do you do when you learn that

someone you loved, someone you have not spoken to for 28 years has died? A

silent sadness lodged in me as I thought of how unhappy he must have been in

this world. I spent one frantic night trying to learn more, wondering how he

died, did he perhaps jump and fall, a final plummet to the earth that shattered

more than his legs? There is no reason I need to know this, and my quest

implies that a death by falling would somehow make this sad end more noble or

right. It would not.

I’m reading the Inferno for the first time. The suicides are

there, in the 7th circle of hell. When Virgil encounters the dead

what they want is to be remembered to those still alive. So this is what I can

do: remember Michael, the way his long skinny legs stepped high for a hold, the

California sky blue, his smile punctuated by a Marlboro that greeted me on

those thin belay ledges. What I can remember is that in that summer of climbs

we shared a love that for me has lasted a lifetime.